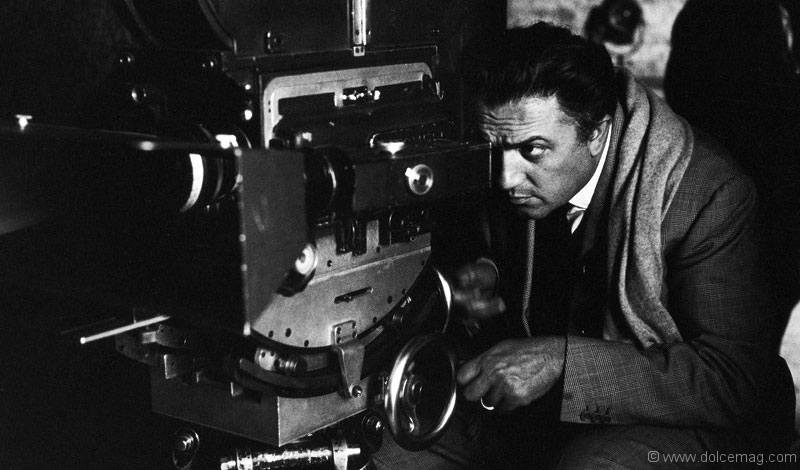

Filmmaker Federico Fellini

As the screen fades to black after Nights of Cabiria, the audience buzzes with praises of “genius,” “innovator” and “classic.” This early cinematic classic by Federico Fellini, one of the most highly regarded filmmakers of all time, was a part of TIFF Bell Lightbox’s “Fellini: Spectacular Obsessions” and Joseph D. Carrier Art Gallery’s “Fellini: The Dolce Vita Years” – exhibitions celebrating the career, achievements and influence of arguably Italy’s greatest filmmaker.

This recent Toronto exhibition showcased the evolution of Fellini’s style, shifting from neorealism to the surreal, subconscious explorations of dreams and fantasy. “Federico Fellini is one of the great masters of cinema,” says Noah Cowan, artistic director at TIFF Bell Lightbox and curator for the Fellini exhibit. “Fellini really fills in the news these days … and I think he can tell us about our celebrity obsessed culture.”

As one of his earlier works, Nights of Cabiria (1957) stems from Fellini’s neorealist roots, where his films were littered with tales of wacky dreamers, circus performers, prostitutes, seducers and swindlers. They revolve around “the provinces,” or about crazy provincials always dreaming and going to Rome, which, of course, Fellini did himself. “He was really actually involved in this whole post-war renaissance of Italian cinema,” says Peter Bondanella, a retired distinguished professor emeritus of comparative literature and film studies in Italian at Indiana University, and author of The Cinema of Federico Fellini (Princeton University Press, 1992).

“What people didn’t understand about Fellini,” adds Bondanella, “was he was actually one of the best scriptwriters in the neorealist period.” In fact, Fellini was nominated for an Academy Award in 1947 for Best Writing, Screenplay for his work on Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City.

His cerebral method was rich in imagination, bringing challenge and criticism, humour and melancholy. In La Dolce Vita (1960), for example – a film which marked a stylistic turning point in his career – not only does Fellini introduce the world to the term “paparazzi,” he magnifies society’s growing obsession with celebrity culture, presenting beauty while exposing the darker, superficial flipside of the ‘the sweet life.’ “In many ways, Fellini sort of anticipated a PR society, a kind of Murdoch sort of world of fake journalism,” says Bondanella. Although often critical, Fellini’s work has inspired fashion designers, hotels, restaurants and publishers to embrace the sweet life, as Cowan explains, “Because of La Dolce Vita he really became a kind of symbol of European style and elegance.”

Throughout his prestigious career, Fellini was nominated for and won a mountain of international film awards. Six of his films captured Academy Awards, including Best Foreign Language film for La Strada in 1957, Nights of Cabiria in 1958, 8 1/2 in 1964 (which also made GQ’s “The 25 Most Stylish Films of All Time” list) and Amarcord in 1975, Best Costume Design, Black and White for La Dolce Vita in 1962, and Best Costume Design for Fellini’s Casanova in 1977. In 1993, he was also presented with an honorary award from the Academy in recognition of his cinematic accomplishments, only months before he died of complications from a stroke.

Today, Fellini’s influence still runs deep. Great filmmakers, such as Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick, Terry Gilliam, Spike Jonze and Woody Allen have all pointed to Fellini as an influence. His powerful, dreamlike imagery and compelling storytelling not only demonstrated his vision and complete understanding of art, but most importantly, showed the world what the power of imagination could do.

No Comment