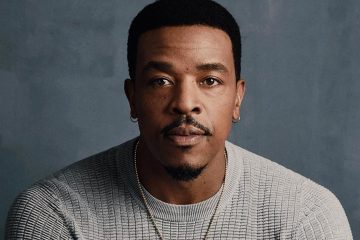

Anthony Hopkins: A life playing kings, captains, Presidents and popes

Living in Malibu, Calif., with his wife, Stella, Anthony Hopkins arrived an hour early to our shoot, located at Robert De Niro’s nearby Nobu Ryokan hotel. Easy to work with and talk to, the Welsh actor’s piercing gaze hasn’t changed since the days ofThe Silence of the Lambs.

In an age where special effects are often used to make older actors look younger, Anthony Hopkins stands alone. The Oscar-winning actor is doing it the old-fashioned way, memorizing lines and bringing his trademark intensity to his new roles, seemingly unaffected by age. Has an actor over the age of 80 ever delivered a performance as earth-shattering as his version of King Lear? Probably not. But don’t count on Tony, as he insists on being called, to explain how he does it. He doesn’t know and is as surprised as anyone that his career is still going this strong at 82 years old. And whether he’s walking on the beach with the Pacific Ocean’s waves in the background, or resting on a bed during the interview, you can’t avoid noticing Hopkins’s strength. It’s the same strength that enables him to play kings, captains, presidents and popes. We sat down with the legendary Welsh actor to find out the secret to his enduring craft.

Q. Do you think success is down to luck?

A. There’s a saying, I think by [philosopher Arthur] Schopenhauer, that when you reach a certain age and look back, you feel your life has been written by someone else. You can’t make the connections. Everything seems to be connected. But I can’t explain it. What I like about it is the feeling that I can’t take credit for anything. It removes the ego. The only conviction I have is that my life is none of my business. I don’t have a clue about it. I’m still pretty clueless.

Q. What do you remember of your childhood?

A. Wales is a small country in the British Isles. In America, often they don’t know where Wales is. It’s understandable. It’s like, ‘Do I know where Lithuania is, compared to Latvia?’ The place where I was born was a bit isolated, a bit cut off, but it’s not anymore. I was there recently. I go back once every few years. It’s nice. But I don’t feel any different than anyone else. I’ve got a different accent. Fifty years ago, it mattered more, because there weren’t many actors from Wales. But now there’s quite a few.

Q. Michael Sheen …

A. He’s from the same town as I am. I met Michael recently, in Wales. But I’m not passionate about these things. I don’t have any identity at all. I’m my own entity. Empty. Most of the time, I feel empty. That’s what happens as you get older. Things begin to empty away. It’s not very important, you know. It’s a great state of mind to be in. I’ve reached that now. Kind of peaceful. Sometimes I get impatient, but not really. I’m mystified as to who I am and how I came here. Now I look at it and think “Well, it’s a good life.” Very lucky. And again, I can’t say I can take credit for any of it. My ego’s gone.

Q. Did your interest in acting start before you were 13?

A. I wanted to be a musician, to play the piano. Something different. I knew that academically, in school, I was zero. During the school holidays, I would go on long walks and wander in the mountains. I was very isolated, I didn’t have any friends. I didn’t play any sports. I was a dreamer. At the same time, I went to ask Richard Burton, who was born in the same town as me, for his autograph, in 1954. Twenty years later, he’s in the same dressing room as me in a theatre in New York. It’s impossible. How did that happen?

Q. Was it an easy choice for your parents to understand?

A. My father was pessimistic. My mother, like all mothers, believed in me. I started being recognized, and they came to see me. They caught on to the fact that I was becoming successful, very successful. They both lived to see my big successes. But I could no more explain it to them than to anyone else. Even at this moment, answering your interview questions, I have no idea how to explain how all this happened. I’ve had a phenomenal life, an extraordinary life, starting from where I came from. So what I’ve learned – I’m going to be 83 in December – is to look back at it as a mystery. It’s a puzzle to me. I can’t believe I’m playing these parts.

Q. Acting is so competitive. Mentoring could be almost impossible. Have you mentored younger actors yourself?

A. I try to help actors. I say, “Stop trying to be cool; it doesn’t work. It’s boring.” They’re so “cool” … lazy. Stupid. I tell them, “Learn your craft, be disciplined.” Being in competition with people is a waste of time. How can you compete? Like the awards. Why? You’ve got five people, happy to have been nominated. You’ve got four losers, pretending to be happy. It’s all bullshit.

Q. But you won an Oscar [for The Silence of the Lambs].

A. I won, yes. I didn’t expect it. It’s OK. I never watch the awards show and I never go to them. Some people take competition so seriously, they become unreasonable to work with.

Q. You’re famous for preparing your roles very thoroughly, but you’re not a method actor per se. Can you explain your process?

A. Well, I learn the text so deeply that it does have a chemical effect in your brain, I think. I’ve been playing some pretty toughs guys. King Lear, and then in The Father, this guy with dementia. It’s exhausting. But I’m not a method actor in that sense. I believe in learning the text which is there. Once you know it so well, you can improvise and make it real, and it’s easy. You just have to be prepared. You can’t pretend that you know it. I couldn’t do it, it would be impossible. And I’ve worked with actors who don’t know their stuff. They’re wasting our time. I’ve just worked recently in Britain on King Lear with Emma Thompson, Jim Carter, Jim Broadbent. It was wonderful, because they’re all so “bomb” [punches his fist into his open hand]. It’s like being in a fight. The technique, it’s like playing tennis. You’ve gotta be an athlete. I know I’m not athletic, but I can still move. I can still punch out. You have to have that strength. And I am strong. I’m very, very strong. And my strength, my physical power, has helped me to survive. You have to look after your health, make sure that you don’t get fooled by people. Because once you start believing that you’re God, that you’re hot shit, you’re dead.

Q. Do you think of yourself as someone who can easily be scary?

A. I know I do. It’s a technique. When I read the script for The Silence of the Lambs, I thought, “Ah, I know how to play this guy.” You get a sense on how you could do it. The more subtle you are, the more quiet you are, the more scary.

Q. Were you worried at all about typecasting, or worried that people would confuse you, Anthony Hopkins, with Hannibal Lecter? Did you experience this?

A. Oh, yes. People say, “You only play scary characters,” but it’s not true. I’ve played many, many parts. It’s one of those things; it was a very popular film. It’s stupid, though. I’ve played President Nixon, the Pope, Hannibal Lecter. I’m none of those people. I refuse to be typecast.

“I feel life is A dream, more So now than Ever before. I look back At my life like It’s all A dream”

Q. One of my favourite parts you played is that of President Richard Nixon. Could you relate to the paranoia of the character? He wanted to be liked, but ended up being hated.

A. That’s why Oliver Stone picked me. He called me, and I asked him, “Why me?” He said, “Because I’ve read you’re very insecure, that you never believed you belong, that you’re an outsider. That was Nixon.” I said, “But I’m not an American actor.” He said, “But you’re good.” James Woods told me “that part is not too far removed from you.” I guess, I like to hide away.

Q. Someone like my 12-year-old son knows you as Odin, from the Thor superhero movies. Did you have to do a lot of green-screen acting?

A. A lot. I did three of them. I like Kenneth Branagh, the first director. Excellent director and wonderful actor. Chris Hemsworth is a terrific actor. He’s an example of someone who’s never been touched by ego. I think he told me he used to eat 2,000 calories a day and take in massive amounts of proteins to prepare for the part. He’s good, and I like him, because he seems very unaffected.

Q. You’ve had a complex relationship with the theatre, sometimes saying you’re too impatient for it.

A. I’m not good at it; I couldn’t do long runs. My relationship to acting is pretty loose. Acting to me is just the thing I do, but in the theatre, you’ve got to dedicate yourself to it. But when I’m working on a big part, like Lear, I give it all my power.

Q. On to The Two Popes. Not many people have played the Pope. Was there a specific preparation for this role?

A. All I had to do was learn Latin and Italian. I worked with Jonathan Pryce [who plays Pope Francis], which was terrific. I didn’t know Jonathan that well. We’d met a couple of times. We just did one job together. I turned up in Rome to work with him. He’s such a lovely man to work with, just easy. He’s the only actor I had to work with. We had Fernando Meirelles, terrific director. Two takes, that’s all he needs to work with. We booked the Sistine Chapel and Cinecittà Studios. You let the scenery do the acting, all you have to do is show up. Just like John Wayne said about his Westerns. “You go to Monument Valley and you let the American landscape do the acting.” And that’s true. Fernando turned it into a very watchable movie. It could’ve been very boring. It’s about the argument between two ideas, done very quickly, with humour, and with a sense of friendship. Because Ratzinger doesn’t trust Bergoglio. Bergoglio’s Marxist, Ratzinger is a conservative. And gradually, I realize that he’s just another human being who has a different idea.

Q. I’ve listened to your music. I felt I knew you better after hearing your music.

A. I compose and I paint. I do it for free. My wife said, “You should paint.” There’s nothing wrong, just to do it.

Q. Do you believe in dreams?

A. I feel life is a dream, more so now than ever before. I look back at my life like it’s all a dream. Can you explain what we’re doing here? You look in the mirror, and think, “Who’s that looking back at me?” Billions of years of evolution, and we’re out here. How? Why? It’s a fascinating question. None of us know. Is this it? It’s all a dream.

Photos By Charlie Gray

Styling By Santa Versace-Bevacqua

Grooming By Sonia Lee

Seamstress: Susie Kourinian