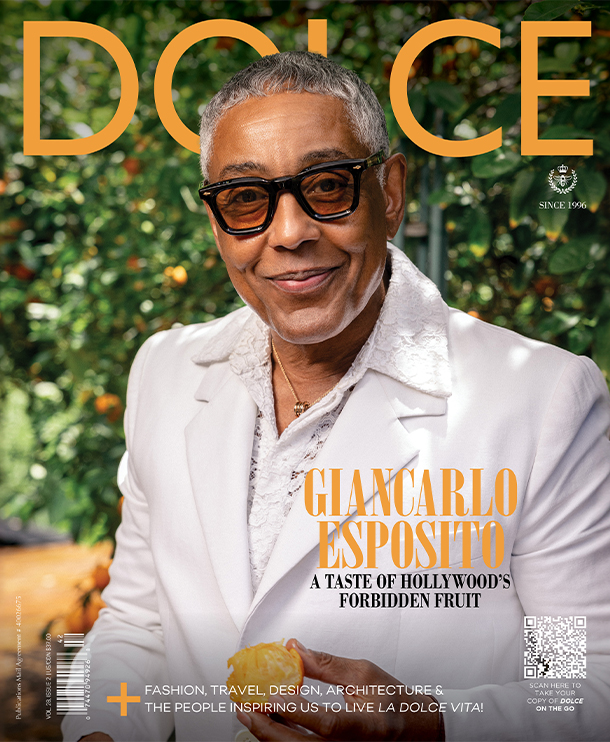

Paul De Gelder: Swimming with Sharks

How a former Australian infantry-paratrooper-turned- Navy Clearance Diver survived a shark attack and became one of the world’s leading shark advocates.

You’re 110 feet under water, surrounded by four of the ocean’s most ferocious predators — the great white shark — as you kneel on a bed of sea kelp. Without the safety of a cage and only the defence of a GoPro stick, the great whites slide out of the murky water directly by your face. This isn’t your nightmare; this is Paul de Gelder’s life.

De Gelder is one of the world’s leading shark advocates and regularly comes face to face with the creatures themselves: “I’m looking at the shark, thinking, ‘If it wants to, it could kill me’ … I could never have imagined that I could hand-feed bull sharks in Fiji or hang out with massive tiger sharks in the Bahamas, but now that I know what to do, there is no fear. It’s a mutual respect. It’s a beautiful shared moment, where this wild apex predator will let you share its environment with it, and that’s why they deserve our respect.”

It’s clear that de Gelder has a great deal of respect and admiration for some of the ocean’s most dangerous predators, which may come as a surprise based on his introduction to the species. In February 2009, while he was serving in the Australian Navy, de Gelder was the victim of a shark attack that resulted in the loss of his right leg and his right hand.

Before the attack, de Gelder grew up in Mornington Peninsula, Australia, with his two younger brothers and younger sister. He had a relatively normal upbringing until his teens, when he turned to self-harming and drugs (drugs came later) to cope with the bullying and discipline he experienced throughout high school.

Fortunately, he found an outlet through Thai boxing as a means to release stress and anxiety. It was a healthy way of coping with his environment at the time, until he took his fighting into the streets, smoked marijuana and drank, which led to him getting kicked out of his home at the age of 17. Throughout his early 20s, he worked in hospitality, but always knew he’d explore the world on a greater scale. So, he joined the Infantry Corps in the Australian Army, becoming a paratrooper in November 2000, and learned how to “hunt and kill people … with the main job to hold ground no matter day, weather, season.”

Successfully passing the extremely gruelling selection process, he went from being a soldier in the infantry unit into the Royal Australian Navy as a Clearance Diver, operationally in the Navy from April 2005 to February 2009.

De Gelder’s attitude toward life is the furthest away from playing victim. Since his attack, he’s been travelling the world, shining a light on the beauty of sharks and advocating for the role they play in our ecosystems. Most recently, he has written a book, Uncaged, which was published in July 2021. The book explores his journey from childhood to now, filled with all of the adventures that have come with his career in the military and as a shark-diving motivational speaker. We spoke with the charming Australian native from his Los Angeles home to understand how he overcame adversity and turned his fears into his greatest strengths.

Q: Can you tell us the motions of the day and what you remember of the day of the attack?

A: We were doing a counter-terrorism exercise. It was me and three of my teammates in a little black inflatable boat we call a ‘zod,’ and my chief, and all the scientists testing the equipment were on the wharf. This is alongside the big Navy base in Sydney right in Sydney Harbour, in the heart of Sydney. You can see the Opera House, the Sydney Harbour Bridge; it’s not way out in the middle of nowhere. So, me and three of my teammates were supposed to be in the water, one at a time, swimming from point A to point B. The goal was to do surface swimming, and then scuba diving, and then rebreathers, which have no bubbles. This automatic detection system was going to try and find us and track us, and so we get too far in the pipe of the exercise. I had my new guy in the water, and, then, about 30 minutes later, I pulled him out, and I jumped in to give him a rest. Within four or five minutes, a bull shark came up from underneath me and grabbed me by the right hand and the back of my right leg in the same bite and decided it wanted them more than I did, and so that was pretty terrifying. You know, I had never seen a big and dangerous shark, and the only thing I was more afraid of than sharks was public speaking, which is very strange because now I’m literally a shark-diving public speaker. But, I was terrified, and the pain was just agony. It was tearing the flesh out of my body while it was drowning me under water at the same time, and I was terrified. But, there was nothing I could do. I couldn’t fight back. It had my hand. It had my leg. And, you really find out how vulnerable you are in the water when an animal like that decides to eat you. So, I just thought I was dead, but eventually the teeth got all the way through my leg and my hand and tore them out of my body. And, while the shark was swallowing and swimming away, I popped to the surface and saw my safety boat in the distance, and so I started to swim toward that, not even knowing that I was injured. And I took a stroke with my right hand, and that was when I saw that my hand was missing, and I didn’t know what was wrong with my leg; I just couldn’t feel it. So, I was swimming back to the safety boat with one hand and one leg, and the guys, my three teammates, in the boat said that they could see I was swimming through a pool of my own blood, and they said it was so thick that they could taste it in the air when they got closer to pick me up. I didn’t think I was going to make it. I thought the shark was going to come back, and I was just waiting for it to grab my ankle and pull me under water and kill me. But, it never came, and the boat got to me first, and the guys pulled me out of the water, rendered first aid as best they could with the minimal amount of equipment that we had on the boat and just tried to keep me alive until the paramedics could get there.

Q: Wow, so was it even on anybody’s radar that there could be animals or something like sharks in the water?

A: We knew that they were in Sydney Harbour, but nobody had been attacked in 60 years, so even though I had sharks on the brain every time I got in the water, you put it in the back of your mind, and you go, “There’s more chance of me dying in the car on the way to work than there is a shark” — then a shark attacks you and eats you …

Q: Was the attack the moment you experienced the most pain or was it the physical and mental healing afterward?

A: I think the most painful bit was the day after the surgery to have the rest of my leg taken off, when the pain medication didn’t work, or it exacerbated it, and I was moved out of my quiet corner of the hospital of the Navy wing and put into a general population area where all I had was a curtain around me. People had visitors, and I was tripping out on ketamine, I was on morphine, and I was in absolute agony. And, all I wanted to do was die for 20 hours. They couldn’t get it under control. I was just rolling from side to side in my bed, bawling my eyes out, begging to die, so those 20 hours were probably the worst of everything, and probably my whole life.

“Sometimes Facing (those) Fears head On is the only Way you’re Going to get Past them”

Q: And what were the next few weeks like after that? How long did it take for reality to set in?

A: Within a day, reality set in. I guess the military is very good at training to disconnect the emotions and just thinking things from a logical standpoint, and I realized pretty much straight away that there was nothing I could do about it. You know, I’m not going to be able to grow my limbs back, and so the only thing I can do is deal with this situation as best I can, and so, instantly, I think, “I’ve got to just dispel this fear with knowledge.” We have the world’s knowledge at just a few keystrokes, and so I got onto Google and thought, “I’m going to need some prosthetics if I’m going to get back to work,” because that was the goal, you know, this was all motivated out of fear. I was terrified of losing my whole career, everything that I had worked for throughout those past nine years or something and becoming that person I was before joining the military. And so people think fear is bad, but it can actually be a very powerful motivator, and so I just did every single little thing I could to try and ensure my best chances to get back to work … I would never be happy pushed under a desk, and so I thought, “OK, if I’ve got to mix it up with these elite athletes that I call my mates, then I’m going to have to train three times harder just to be half as good.” And so it was very basic steps and very small achievable challenges and goals in the early days. What do I need to do? OK, I need to get really fit. I need to learn to use my body again, and I need prosthetics to help me … I started looking for the best and greatest in prosthetic technology. Then, I went to YouTube and started looking up Paralympic athletes and how they did their things, and, so, throughout all of these avenues, I started to create self-belief. As unrealistic as it seemed at the time, that was all I had to hang on to, small achievable goals to get me to the impossible dream at the end.

Q: Wow, and what would you like people to learn from your shark attack, and where you are now?

A: If you had asked me previous to the shark attack if I would rather lose two limbs or die, I would’ve said I’d rather die. And then something like this happens, and you realize that it’s not so bad. A lot of the times, most of the time, we create scenarios in our lives and in our minds that are actually far worse than anything we’re actually going to face. We diminish the life and the ability for us to achieve remarkable things just by having that internal dialogue that repetitively gives you that negative mindset, so we need to be very careful about that internal monologue that we feed ourselves. I was very fortunate that, after joining the military, I had trained myself into believing in myself because it was so hard to get into the areas of the military that I got into. Through selection processes, I had to say to myself, “You can do this, you can do this, you’re strong enough, you’re good enough.” And so I practised that over and over again and so that had come into play in my recovery. So, if we can all sort of practise that internal monologue, that positive self-speak, then we’re going to have a better chance at creating the lives that we all want. And I think that’s part of the reason why a lot of people, depression and anxiety and suicide are all off the scales these days, and I think it’s partially because we don’t have that great internal monologue. We’re not pumping ourselves up, and we can’t rely on social media and comments and likes to have other people to tell us this stuff. We have to do it for ourselves, and then, then we can do it for other people, and we can lift other people around us. But, it’s kind of like not looking after your body, eating unhealthy food, not working out and then expecting yourself to look after your kids and family and for them to be healthy and fi t and strong. You just can’t do it. You need to look after you first, and then lift up everyone around you.

Q: The idea that you’re advocating for the thing that took parts of your body from you is just so beautiful. What was that process like when you decided to start advocating for these creatures?

A: I never blamed the shark. I was mad at it. I was pissed at it, but, like I said, I’m a very realistic person, and I chose a dangerous life. I’m riding a big, black Italian sports bike, I’m jumping out of aircraft, I’m playing with explosives under water. I’m doing all manner of crazy dangerous stuff. You can’t choose that path and then get upset when something goes wrong. That’s the path you chose, and it could’ve been any number of things. At least this way, I get a cool story, it gets me free beer at the pub, and so that’s a win, as far as I’m concerned. And I didn’t really want to have anything to do with sharks after that. I just wanted to get back to work, and so that was my entire focus, but because [the attack] was so high-profile, every time there was another shark-attack interaction around Australia, the media would come to me for a comment. And, I started to learn about sharks out of necessity because I wanted to be able to give an educated opinion instead of just an opinion. So, I started to learn. Once again, the greatest tool is the fact that we have the Internet. I can get on Google, and I can Google sharks, and I can learn all about them, and that was when I discovered that we, as humans, are killing over 100 million sharks a year, and, by comparison, sharks kill maybe 10 people in the whole world every year, and so that made me realize, who should be afraid of who?

You know, my military career was all about protecting those who can’t protect themselves, and to stand up for those who can’t stand up for themselves. And so I saw this as an opportunity to continue this ethos in another realm and speak up for these animals that don’t have their own voice, that are vitally important to the oceans, and they just don’t deserve to be slaughtered like this. They’re just going about their business being sharks … They have a very important position in the ecosystem that keeps our oceans healthy, and if we keep destroying our ocean the way that we are, it’s going to reach a fulcrum point where it’s going to tip over the edge and there is no return. And it will just die, and then we die next, so we’re actually looking after ourselves by looking after the oceans, looking after the sharks, looking after the fish. The ripple effect always comes back to us, and so we need to be a little bit more cognizant about what we’re doing to this one single home that we have that is on a steady decline.

Q: What would you say are some of the biggest misconceptions when it comes to sharks?

A: Maybe the fact that people think that they’re just sitting there waiting, and lurking, to eat everyone, but they’re not mindless killers. You dive with some of these big sharks, like great whites and tigers and bulls, and you can see the intelligence in their eyes. And, especially with great whites and tiger sharks, they all have different individual personalities. We have sharks that return to the same place every year, and you can always tell who it is by the personality. And, they’re just beautiful animals, and I’ve taken some of the most famous people in the world diving with sharks — Mike Tyson, Will Smith, Ronda Rousey, David Dobrik — and every single one of them was scared, but every single one of them came out of the water saying it was one of the most incredible things that they have ever done in their life, and their whole perception on sharks had changed. And so sometimes facing those fears head on is the only way you’re going to get past them.

Q: Why do you think Hollywood is obsessed with sharks?

A: I don’t think Hollywood’s obsessed with sharks. I think that they are obsessed with finding stories to scare the crap out of people for entertainment, and I love watching these shark movies. I got to interview Blake Lively and hang out with her for The Shallows, and I got to hang out with Ruby Rose and Jason Statham and interview them for The Meg. I thoroughly enjoy those shows. I’m more concerned about those people who can’t tell the difference between a documentary and a Hollywood movie than I am about sharks. But, they’re an animal, that, even though most people are terrified of them, most people will never, ever see them with their own eyeballs in their entire life. And so I think that’s something that Hollywood loves because they can play on that fear that people already have inherently in their soul. But then you can tune into Shark Week and watch the actual facts of these sharks that are actually really amazing animals and a beautiful part of the ecosystem.

Q: Can you tell us about your vegan diet and why you have made that choice?

A: I started about four and a half years ago, and I’m just a firm believer that, when the universe is speaking to you, you need to listen, because it’s for a very important reason. And so I didn’t really know anything about it. Then, I went to Africa to shoot a documentary with a friend of mine called Damien Mander, who runs the International Anti-Poaching Foundation. He has a wonderful documentary called Akashinga, which means “the Brave Ones,” that’s about his entirely female-run anti-poaching unit in Zimbabwe. It’s an amazing documentary about some incredible women, and so I was working with him, and he started talking about it. He was eating from a different pot to his rangers, and I thought he was saving the meat for himself, and so I was being cheeky, saying, “What’s up with the separate pot?” And he was like, “I don’t eat meat. The rangers eat meat.” And it kind of took me off-kilter. I expected the opposite, and I said, “Why don’t you eat meat?” And he said, “Well, I came out here to protect these animals, and then I was going home and I was eating these animals, and I felt like a hypocrite.” That struck a bell with me because I dislike hypocrites thoroughly. The worst leaders that I’ve had in the military were always hypocrites, the “do as I say” sort of leader, not the “do as I do,” and so I always strive to be a leader by example. I would never ask anybody to do something that I wouldn’t be willing to do myself … And so I started looking at the health benefits, the ecological benefits, the environmental benefits, the torture and the suffering that these animals go through, and it basically made me think that there’s no reason not to do it … The only reason I could think of not to do it was because I was scared I’d become a smelly, skinny, tree-hugging hippie, and so then I started meeting bodybuilders and really fit athletes that were vegan … Four and a half years later, I love it. It makes me feel good in my soul, and I think that’s the most important aspect … to be able to maintain something like this and it’s just not necessary. Some people aren’t willing to think about what they’re doing. They’re not willing to progress to another level of compassion … People are just disconnected from their environment that they live in. They don’t have compassion for these animals that deserve it. No living creature, as far as I’m concerned, deserves to go through a life of cruelty, suffering and torture, and that’s exactly what happens to these animals.

Q: If you were to be a shark species, out of the more than 500 that exist, which one would you be most like and why?

A: I’d probably be a cookiecutter shark because they just sneak out of the depths and grab a bite of food, and nobody even knows they’re there, and you can just sneak up. I like to eat, and so the cookiecutter sharks were first discovered when the U.S. Navy were bringing their submarines in for refits, and they kept finding all of the cookiecutter-shaped chunks out of the rubber dome on their sonars, and they couldn’t work out what it was. It was these tiny little sharks called the cookiecutter shark, and they do it to whales and everything. They just sneak up to everything and take a cookiecutter bit out and take off. I think that would be me, sneaking to get the food.

Q: Where’s your favourite place to travel to and why?

A: Wherever the adventure is. I don’t really have any favourite place. Just like I love all sharks for the beauty and the differences of each of them, every other place that I go to has another aspect that’s amazing about it. I just love travelling and seeing new cultures and new places.

Q: What does your family think of your career now?

A: I’ve never asked them. I think Mum is just really proud, probably Dad, too, after where I started out. They probably didn’t have very high hopes for me, and so now I’ve done really well. I excelled in the military; they’re all proud back there, I’m sure. Now, taking what happened to me to another level and creating another whole life, I think they’re pretty proud. I think my brothers and sister think I’m crazy. I think most of my friends think I’m nuts.

Q: How would your 10-year-old self react to what you do now?

A: I would be my own hero, absolutely. I literally get to walk in the footsteps of my own heroes now, like Alby Mangels, the Leyland brothers, obviously Steve Irwin, Ron and Valerie Taylor — you know, those are the people that I loved watching growing up. Now, I get to do exactly what they did, and it just makes me so happy.

Q: Where do you feel most at peace?

A: Under the water, in the ocean. I don’t understand why people don’t want to scuba dive because they get claustrophobic, whereas I have the total opposite feeling. It’s so open and just vast, and I think there’s no other way to be totally encompassed by nature as when you’re under the water in the ocean, breathing like one of the fishes, hanging out with weird aliens. It’s like going to space, an alien environment. There’s all these little alien creatures swimming around you. You’ve got to have a breathing apparatus. It’s the coolest thing ever. It’s so relaxing and peaceful; no one can talk to you, there’s no social media. You can just hang out with fish.

Q: What’s your definition of pain?

A: Going through life without finding value or purpose.