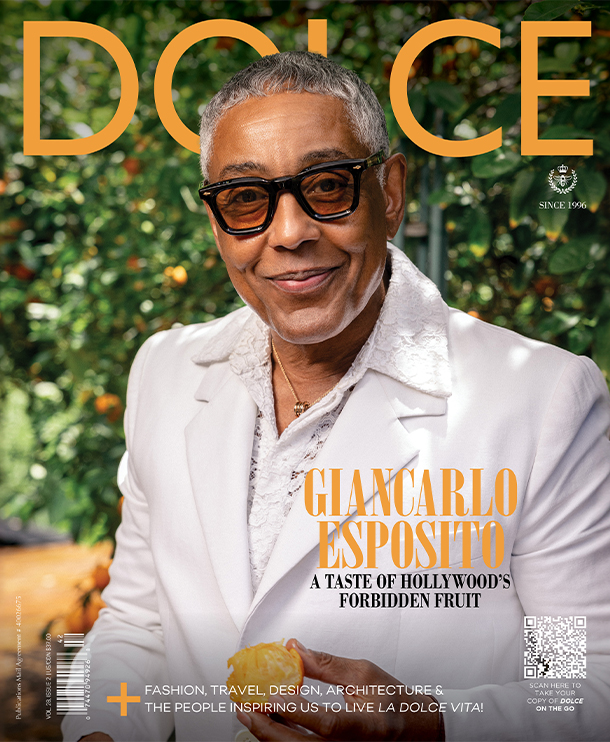

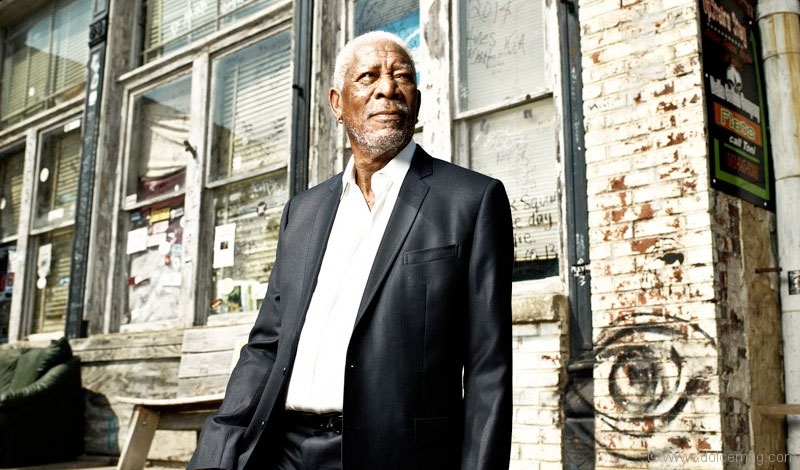

Morgan Freeman

There’s more to love about Morgan Freeman than his smooth, deep voice and award-winning performances. The acclaimed American actor and best-known narrator shares his love for the blues and living life away from the bright lights of L.A.

When word got around that our photo shoot and interview with Morgan Freeman would happen in the small town of Clarksdale, Mississippi, everyone was surprised and almost shocked. “What’s he doing in Mississippi, is he making a movie there?” “What, he lives there? Doesn’t he live in L.A. or New York?” It seemed impossible for people to believe that such a huge star would live in the middle of the Deep South, in the Delta region. But to me, there was something so cool about the man who had played God living where the “Devil’s music” — as the blues had once been labelled — grew up.

Clarksdale is a small town of about 18,000 people and is located an hour and a half south of Memphis. It’s where blues legends like Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Ike Turner, Robert Johnson and countless others developed their musical craft. Robert Plant and Jimmy Page from the band Led Zeppelin named their 1998 album Walking into Clarksdale as a tribute to the city’s musical heritage.

At the very edge of Clarksdale, after driving across a small countryside town, past the cotton fields and the Mississippi riverbanks, you’ll find the Ground Zero Blues Club. To foreigners’ eyes, it could pass as a saloon in some old Western movie, except for the stage in the middle of the hall where bands play almost every day of the week. The appearance of the place isn’t modern — there is some authenticity to be found and all the walls have been written on. At 9:30 a.m., while the photography team sets up, a Porsche parks right in front of the venue. Not long after, Morgan Freeman pushes through the front door, arriving on his own.

Taller than most and wearing a suit, there is no mistaking the man who has won an Oscar in 2005 for the movie Million Dollar Baby and has been nominated numerous times for Best Actor. The stylist proceeds to show him the clothes, but immediately he replies: “What do you mean, the clothes? I’m already wearing a nice suit, why do I need to change?” Everyone is taken aback only to realize that Freeman is joking, talking in a very serious manner as he often does, but with a twinkle in his eye, to let you know that in reality he’s just being playful. After sharing numerous anecdotes, including how he arrived in New York from Mississippi with $300 in his pocket when he was in his early 20s, only to spend it all on dance lessons for him and his friends, Freeman opens up a bit about his fashion tastes. “I’m not a fashion person, I only own two suits,” he confesses. But he says this while wearing Salvatore Ferragamo shoes and a Dolce & Gabbana tailor-made suit! Not bad for someone who doesn’t like fashion. “My favourite designer is Giorgio,” he adds. There is no doubt that he means Armani. After this, Freeman asks me to have breakfast with him. What can you talk about when you’re having breakfast with a man who was God (it was in a movie, I know)? Well, anything and everything, as there is almost no topic you can’t discuss with the iconic actor.

THE BLUES

Q: We’re doing the interview here at the Ground Zero Blues Club in Clarksdale. This is where, as legend has it, famous blues pioneer Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil in exchange for mastering the blues. Why did you decide to open a blues club? Did you have any reason to open it here?

A: I started hanging out with Bill [Luckett, his business partner] after meeting him in 1996. He and I both noticed that there were a lot of people in Clarksdale from out of the country wandering around the streets saying, “where can we find some blues?” Bill has always been a very big ambassador for Clarksdale. There was a little place called the Crossroads that would have some of the blues guys play, but there was nothing stable around. So he decided that “this place needs a real downtown joint, a real blues club! I’m gonna find a building.” I said, “Why don’t you let me help?” He said “sure.” Anyway, we found this building, and he decided on the architecture. It looked pretty much like it looks now except for the writing on the wall, the plaques. He didn’t want to make it look like … it had to look like an old juke joint. This was twelve years ago, in ’02. That was the genesis of Ground Zero. We also had a very nice restaurant for ten years, but it never made any money so we closed it.

Q: You live not very far from where you grew up, in Tennessee, and then in Mississippi. Why did you choose to settle here? Do you feel a special connection to this region?

A: It goes back to my great-great grandparents. Probably further back than that. But that’s as far as I was able to track it. My grandmother was born in the Delta, my mother too. My biological father and my stepfather were born there too. I have deep roots here.

Q: That’s why you moved back out here?

A: No, that’s not really why. I did a lot of travelling myself. I left when I was eighteen. In my travels, it occurred to me that this whole racial issue in the United States, we didn’t have … we weren’t the capital of it. It’s everywhere, almost.

Q: It wasn’t unique to Mississippi.

A: It wasn’t. So my parents moved back from Nashville, in ’56 or ’57, bought some property not far from where I grew up as a little boy. My second wife and I started coming to visit in the seventies, and every time we came here, I had the same feeling of comfort I had as a child. And I thought, “this is the best place in the world!”

Q: I interviewed Robert De Niro and he said the same thing — his office is very close to the neighbourhood in New York where he grew up.

A: I had to decide where I was going to put roots down and build a house. I lived in New York and really got sick of New York; I was getting actual stomach pains from the tension and the stress! That was in the eighties, when things were changing so rapidly. I lived on the Upper West Side. There was a wonderful neighbourhood there for a little while. Then we started getting this gentrification movement. The oil crisis in the seventies started putting landlords in a bind. They couldn’t sustain buildings. In New York, they had rent control — you couldn’t raise the rent. If you can’t raise the rent and everything else is going up, pretty soon a building is a loss. All those old people living in those rent-controlled buildings were now at loose ends. It was in the eighties that New York became one of the capitals of homelessness. Not a good place to be. But coming down here was like moving to paradise! We did this in the mid-eighties.

Q: You decided to open a blues club. Are you a blues fan yourself?

A: I’m a music fan. Yes, I’m a blues fan. I grew up with this music in the Delta. All those old blues guys. None of the guys that play here at the club are as old as I am, but they remind me of the guys who were playing just like this — amateur guys who played guitar, sitting on the front porch or the back porch drinking moonshine, playing the blues [Laughs].

Q: Do you have a favourite blues man?

A: It used to be … argh! [Silence] … I just learned that when you get as old as I am, we can’t remember stuff. Not because we’re getting forgetful, it’s just that there is so much stuff up there [Points to his head] that you got to go through before you can find it!

Q: There are some murals of great blues musicians all around Clarksdale.

A: Muddy Waters and B.B. King are from here. We just lost a great one a few years ago, Pinetop Perkins. He was ninety-seven years old. Bobby “Blue” Bland, that’s the guy I was trying to think about. Albert King, of course.

Q: Being here reminded me that the blues started in a rural setting, before moving to the cities.

A: Blues started in cotton fields. Did you see the picture Ray?

Q: Yes, I like that movie.

A: There you can see the marriage between blues and gospel. That’s how rock was created.

Q: Very few movies have been made about the blues.

A: Not a whole lot. A couple of them, but they weren’t that successful. There was one with this kid Ralph Macchio.

Q: Crossroads in the eighties.

A: Yes. Ry Cooder played the blues man … there probably will be a new movie made about the blues. I read these two scripts about young white guys coming down here looking for old black guys …

Q: Would you consider playing a blues musician in one of those movies?

A: Yes, I was going to.

ACTING CAREER

Q: Your filmography includes just about every genre available. What has taking on such a variety of roles taught you as an actor? Has it influenced you as a person?

A: It would be hard to say it didn’t. But I couldn’t tell you what!

Q: What has your favourite part been about being an actor?

A: The favourite part of my job? When they say “that’s a wrap” I’m a happy camper.

Q: Some actors like to be extremely method when portraying a character. How do you like to prepare for a role?

A: I’m not a method actor at all. I just learn the script and go for broke.

Q: One of the things I was thinking about, maybe specific to you, is that you got more interesting parts as you got older …

A: I was old when I started! I was fifty, maybe forty-eight or forty-nine, when I got my first movie role, my first good movie role. Prior to that I was on stage — nobody knew me outside of New York. But toward the end of that twenty-year period, I had a pretty good reputation in New York. Then I got into the movies, with a picture called Street Smart with Christopher Reeve that sort of launched my movie career. But, boy, I’ve been around a while!

Q: Most actors dread getting older, they think the roles are going to stop coming. Maybe time was an ally …

A: Maybe that. The difference between men and woman is that men have much more longevity.

Q: Only Helen Mirren and British actresses seem to be able to push back time.

A: Helen Mirren, Meryl Streep, people like Julia Roberts, she’s doing well. Because there are roles. But conventional wisdom in Hollywood is that once you get past forty, nobody wants you. That’s not really true. You just can’t get the beauty queen roles. But if you’re really a terrific character actor, there are those, Meryl being the top of the heap, that can work. There is so much work available. Now you got Netflix, for Chrissakes! There’s work to be had!

You just have to relax and go with the flow …

Q: Now that you’re one of the most established actors in the business, you can be selective of your roles. What usually draws you to a specific character? Is it the script? Or the director?

A: It’s not so much the director, although there are situations now where I’m doing things for directors. But it’s primarily script and character, what is the story, is it really inviting? After that, who is in it, who is directing.

Q: I was thinking of the irony of you, a believer in science, being asked to play God in a movie …

A: Ah, ah. But they chose me to play God in a comedy, two comedies, actually. If I was Evangelical, I don’t think they’d ask me to be involved in a comedy where God was a major character.

Q: How do you approach playing God?

A: Learn the words. There is no way you’re going to say, “Now I’m going to play God, what am I going to use as a template?” [Laughs]. Where do you go to find out about God? There is no place. Be yourself.

Q: Your voice is lauded as one of the most iconic and sought-after in the business. You’ve done a lot of voice-over roles. One I remember the most is March of the Penguins.

A: Oh yeah. That was a big success. It was such an amazing story.

Q: Was there a point where you realized, “Oh, people want my voice?”

A: No, I had no idea. I did the voice-over for The Shawshank Redemption. After that, people started wanting me to do voice work. Then the whole “myth” about my voice being … “unique” … no voice is unique!

Q: I used to be a singer in a band and I remember other singers having techniques to maintain their voices. Some wouldn’t talk two hours before a show or would add honey to their tea. Do you have any tips to take care of your voice?

A: No. The biggest thing for the voice is relaxation. After that, I don’t know about anything. Stevie Wonder drinks honey and cinnamon. He gets a cup of tea loaded with honey and then adds cinnamon. I heard it’s very good for the health. I don’t do anything out of the ordinary; I take vitamins.

Q: You’ve done a number of movies with Clint Eastwood. [Freeman makes the number three with his fingers, for the trio of movies he did with Eastwood]. Do you have a special connection with him, a reason for going back to him?

A: My special connection with him is that he’s one of the best directors, and one of the best to work with. I like the way he directs. He doesn’t direct actors — he directs a movie. If he hires you to be in a movie, then acting is up to you. He’s very quick. [He chuckles]. He has a certain unique way about him that’s very endearing to most actors. Everybody I know who’s ever worked with him adores him.

Q: He was a great actor and became a fantastic director.

A: He’s been directing a lot longer than you would think.

Q: He started in the seventies.

A: Yes, Play Misty for Me was the first movie he directed. And it seems that whenever he plays a movie, he plays a vulnerable character.

Q: True. And he often makes fun of his tough guy image. Like in the movie Gran Torino, which I thought was fantastic.

A: You got this tough guy … he’s not a tough guy, he’s a meanie! He’s intolerant.

Q: Then you find out he has a big heart underneath all that …

A: A lot of those people do, if you can just get to it.

Q: That’s a movie where the main character is not in the typical “leading man” age range. But it works very well.

A: Yeah, but now he’s taking on these parts where he’s aging. He’s not trying to dye his hair black and be Stallone or Schwarzenegger. Schwarzenegger is going to do Terminator 5!

Q: Our photographer Marco just shot the Terminator 5 movie poster last week!

A: Those are his best roles because they don’t call for any acting. [Freeman then does a very funny Arnold Schwarzenegger imitation].

Q: The movie The Shawshank Redemption has a particular resonance in many countries around the world: two men fighting a corrupt system and winning in the end. Do you have an idea why this movie still moves people twenty years later?

A: Only the white guy beat the system. The other guy spent his whole time in the prison.

Q: Maybe you just get this feeling while watching the movie that they both did it.

A: That is a feeling, maybe the redemptive part of the movie. But only one got redemption. The innocent man. The guilty man served his time.

Q: So you think it’s a more conservative movie than is generally thought?

A: Well, yes.

Q: But they did share the money …

A: I wish I had some of the money the movie is making! [Laughs]. It’s probably the most-watched movie on television ever.

Q: Do you still go out of your way to see new movies?

A: I saw a Chinese movie, a short movie, recently. It was late at night. It couldn’t have been more than twenty minutes long. It was in inland China. This guy goes out on the highway. This bus comes along. He flags the bus down. He gets on the bus. There’s a woman bus driver. Cute, young lady. He tries to make a pass at her; she says, “Go sit down.” So he sits down. Then the bus is flagged down, three guys come on the bus. And they rob the bus, the people. They take the bus driver, the young lady, to the nearby woods and rape her. The people on the bus are sitting there. The guy says, “What are we doing? They’re raping her! We have to do something!” So he gets up and runs out. Another guy gets up but his wife grabs him. So he runs out and attacks the guys. They beat him and stab him. They finish with the girl and they go away. She gets up, goes back to the bus. He also tries to go back to the bus. She closes the door. He bangs on the door. She tells him, “Go away.” “But I’m the one who helped you,” he says. She goes back and gets his bag, throws it out the window. The bus takes off. He’s walking. Another car comes along. He flags it down. It stops. And just as they take off, cops come by. [Freeman makes siren noises imitating a police car]. They get around the curve up there, and the bus has gone off into a ravine.

Q: The movie ends that way?

A: He realizes the woman wouldn’t let him on the bus because she was going to kill everyone on the bus who didn’t help her. She saved his life.

Q: Can you talk about the movie Lucy?

A: Primarily, the subject matter is “what happens if you’re able to use more than the standard amount of brain power that humans use?” which is 10 per cent. What happens if you could use more? Scarlett Johansson’s character gets a drug that starts expanding her brain, she can get more and more of it. I play a professor of neurology who is very interested in the subject of the brain. She comes to me when she realizes what’s happening to her, and then it goes from there.

Q: Many of your roles are that of a wise man or a sage. Your character in Lucy is a professor. What attracted you to this particular part? How does this role differ from your previous roles?

A: Well, I had lunch with director Luc Besson at his home in Los Angeles. He called me on the phone and told me he had this new project and he wanted me in it. I’m a big fan of Luc Besson, so it was a shoe-in!

Q: Lucy marks the second time you work with director Luc Besson after the movie Danny the Dog. How did it feel working with Luc Besson again?

A: It was the first time I worked with him as a director. I had worked on a movie where he was the producer before, but he didn’t direct that movie. This time he did everything.

Social and Environmental Activism

Q: You have spoken out many times about our planet and environmental issues. What do you think are the most pressing issues at hand? What needs to be addressed and changed as soon as possible?

A: Population reduction. There are now over seven billion people on the planet. And if you fly around the world, you’ll see there’s a lot of uninhabited space, but it’s uninhabitable. There are no people there because there is no way to sustain life. Some of it is covered by ice; some of it is desert covered by scrubs, sands, etc., particularly in Africa, Australia and China. All the other places are overstuffed with people. The way we live now, with longevity, the population growth is speeding up. We’re actually already straining Earth’s resources. I had an epiphany the other night: what if global warming is not just from the outside, but also from the inside? The Earth’s core is molten metal, iron. We have almost from the last one hundred years sucked oil out of the planet, again and again. What does the oil do for the Earth’s mantle? Suppose it’s a buffer, suppose it’s a heat disperser and suppose it’s something that ameliorates the core temperature of Earth so it doesn’t bleed so much to the surface. And now it does. There’s no way to stop global warming, if that’s at all true.

Q: They’re trying to find alternative sources of energy.

A: The people responsible for it are not in a big hurry, because everything is pretty much petroleum-based. And I just heard this morning about the dangers of fracking. That shit is now getting into the water supply.

Q: They do a lot of that in the Rocky Mountains, here in America.

A: All over the place! And coal mining, where they just cut the top off of a mountain and put the stuff in the valley and rivers. They say it’s all in the name of energy, but it’s actually all in the name of money. The people who we hold responsible, Mobil, Exxon, Shell Oil, Standard Oil — all of those different companies are now just two or three. These conglomerates control governments — governments don’t control them. We’re pretty much at the mercy of them. Right now, they could put wind farms in the ocean, not off the deep end, but in the shallow parts. They could easily put wind generators out there. They’re not doing that yet.

Q: You see those wind farms more in the flat areas, like between L.A. and Vegas.

A: And Las Vegas has these giant mirrors now, right outside the city. Have you seen those?

Q: I have. I was there in March.

A: I fly that way, I don’t know how many times a year, but often. It’s dramatic. It’s amazing. They’re probably running half that city with those. But the main point of your question: what do we do about it? The biggest problem is this: human existence. We’re polluting everything and we’re over-fishing the oceans. We’re moving out everything else that lives, or killing it. We’re turning everything on the planet into food for humans! People complain about mountain lions killing their pets here. But that’s because they moved up in the mountains where the mountain lions live! They’re the ones that have been pushed out. There pretty much won’t be anything left but humans. And then what?

Q: Isn’t there hope that humans could do some good and reverse the damage?

A: No. Every form of life has only its own existence at the core of its being, but it turns out that it also needs something else to survive; there is a dependence on something else. In order for that “something else” to live, we form a kind of symbiotic relationship, like bees and flowers, hummingbirds and birds. There are plants that, because they need nitrogen, they will summon birds, so the birds will come, and not only will they eat the flowers and seeds, their guano will contain the nitrogen the plant needs. That’s nature’s evolutionary way of going on. The only thing outside of that system is us. We don’t do that. We’ve cut down most of the forest around the planet. What’s left? Parts of the Amazon, parts of the Borneo rainforest? The scientists say, “these are the lungs of the planet where we create oxygen.” Now what we’re creating more of is carbon dioxide.

Q: The problem is that from the perspective of emerging countries, they say, “We want to live like you, you created those huge cities first, but now we want to have big TVs, good cars, nice apartments and houses. But you’re telling us we can’t have it?” If everyone on this planet lives and pollutes the same way as Americans, there will be no more Earth left!

A: They’re trying, they’re on their way. China is becoming an economic giant, so it needs consumers. People have money and they’re buying cars. We’re not telling them, like you say, “you can’t have it.” We’re telling them we want you to have it. We want you to buy cars.

Q: You are the host and narrator of the show Through the Wormhole with Morgan Freeman, which tackles a lot of large and complicated questions. What was it that drew you to this production? Do you help contribute to the questions that are asked on Through the Wormhole?

A: It was kind of serendipity. Some years back, my producing partner and I started a company called ClickStar. That was kind of a bleed-off from the music thing, Napster. It was in reaction to that. We thought: “The same thing is going to happen with movies, someone is going to come up with a way to just download movies.” We started a company whereby you could download movies, but digital rights management would be a big deal — you could download it, but you’d have to pay for it. There would be no way for you to share it. You wouldn’t be able to download a movie and put it on a disc and then give it to someone. Couldn’t happen. We were way ahead of our time, by about maybe ten years.

Q: The download speed of Internet connections was probably still too slow for this back then.

A: Yes, for one thing. But we also had incorporated in this that we would have channels available for documentaries. I was going to have a channel on outer space. The solar system, plus the universe. Just for people to talk about. Of course we went under with that company. My partner was talking with a lady from the Discovery Channel and just mentioned it. She thought it was a great idea. So that was the beginning of Through the Wormhole.

Q: Do you contribute to the questions?

A: I contribute to everything. Not the answers, though, just the questions!

Q: Your love of science is clear through your collaboration with this show. What do you have to say to those who don’t find it interesting or compelling? What do you think the common person could learn if they were more engaged in science?

A: I don’t know how that came about. I’m an actor. I’m completely right-brained. I don’t do math at all. You get past “1 + 1 = 2,” and I’m stumped! Stuff like algebra, calculus, geometry … none of that actually resonates with me. To say I love science is truly a misrepresentation. I like the science of physics and cosmology, and I like the theoretical stuff you can come up with about the universe.

I had an argument with a physicist. It’s about my own belief. The argument has to do with the expansion of the universe. We thought the expansion would be slowing down by now, but it’s increasing, it’s speeding up. This brings up the question of: is there a difference between space and the universe? And the physicist said no, space and the universe is all one thing. If the universe is expanding, what’s it expanding into? They say, “no, you don’t understand.”

Q: Finally, a totally different topic. You once asked an interviewer on TV to stop thinking of you as a black man and you would stop thinking of him as a white man. I was very impressed by that.

A: That was the TV show 60 Minutes, with Mike Wallace.

Q: Do you think if we stop labelling people, it will bring everyone together and improve things?

A: Yes and no. The world used to be a really, really big place. If you think about what’s happening around the world right now, the stuff that’s happening in the Middle East specifically, and what’s happening between Russia and the Ukraine. Many years ago that stuff was already going on, but we didn’t know about it. News didn’t travel as fast. Nothing is new except we now know about it. The whole thing about relationships, racial, religious — they exist just because. You see these nature shows about chimpanzees? They’re war-like. They kill and eat. We’re not very different, except we don’t find humans that tasteful!

Q: We’re only a few chromosomes apart from chimpanzees …

A: We’re ninety-nine per cent the same as them. So we may not be programmed for peaceful existence. Here in this country, we started with a premise that, two hundred and thirty-eight years later, we’re still struggling to realize, to make true the idea that all men are created equal. If all men are created equal, then you and I don’t have anything to argue about, in terms of who is better. It’s ridiculous, it’s always been a ridiculous argument among humans, but we insist on having it. If you look at India, India is maybe a hundred years behind in regards to the idea of all men being created equal. They have a caste system that works very well for them. Slavery, for example, was the wrong system for this country [the U.S.]. Either you live up to your premise or you have to scratch

it out.

Q: I’m from France and we’ve had that same type of struggle.

A: Yes, your premise is “liberté, egalité, fraternité” [freedom, equality and brotherhood]. Speaking of France, I want to remake the movie The Three Musketeers.

Q: They made so many versions of The Three Musketeers …

A: But they never made the right one! I want to tell that story from Alexandre Dumas’s point of view. Three mixed-race guys, brought from the colonies, raised at the court of Louis the XIIIth among the best, well trained. They stuck together, like birds of a feather. Then comes the new guy, d’Artagnan, who wants to join them, to be among the best. You could use the analogy on the basketball court, same thing with the Count of Monte Cristo. I would make him a half cast. One more reason to be pissed off! I’m coming up with that idea. I can push it — I have a film production company!

photography by Marco Grob

No Comment