Yusef Salaam: Beyond Justice

A young woman is brutally assaulted and raped in a park. Five Black and Latino youths are arrested, convicted and imprisoned. Originally known as the Central Park Five, they are now the Exonerated Five — when an inmate confessed to the crime, the convictions were overturned. Their story has been told in a documentary, a Pulitzer Prize award-winning opera, and a 2019 Netflix series that has been viewed by millions around the world. Now, more than 30 years later, one of the men, Yusef Salaam, has penned a book, Better, Not Bitter (Grand Central Publishing, New York, 2021), filled with not anger, not bitterness, not vindictiveness nor recrimination. Instead, the pages flow with words of hope and inspiration.

The following story contains vivid and gory details of brutal crimes.

Yusef Salaam was waiting in the courthouse while a jury deliberated on his fate. He really believed they would render a verdict of “Not guilty.” Hope died for him that day, and it would be years before it was resurrected. But it did. “My life did not begin or end that day; my life is more than the sum of the worst thing that ever happened to me,” he writes in Better, Not Bitter. “You and I were born on purpose and for a purpose.”

He wrote the book to tell us about the foundation laid by both his family and his faith in Islam, which he says ensured he would not only survive this awful injustice, but also thrive in the midst of it. When the cell doors shut, he knew that if he was not careful to protect his mind and his heart, he could become attached to the process of getting his nourishment from a system that didn’t care about him at all.

You may wonder how an innocent man keeps hope alive behind bars. It is in prayer that Salaam found his greatest inspiration. Beyond this, basketball, art, meditation and poetry … sometimes the lines would just come to him as he was walking down a corridor in the prison. “The Central Park jogger case is actually a love story between God and His people about a system of injustice placed on trial itself, then toppled, in order to produce what amounts to a miracle in modern time,” he writes.

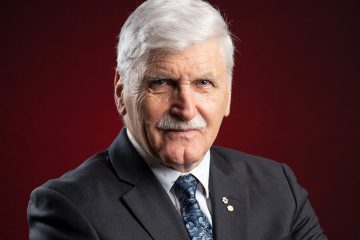

Today Salaam is based in Georgia, just living his life. He follows a vegan diet as much as he can and always looks for healthier options on restaurant menus. He found love in a Starbucks coffee shop, and he’s happily remarried with 10 children. “Here we are 14 years later, with a beautiful blended family,” he says. His son, named after him, was born on his birthday, “so he is a Junior in the truest fashion,” he laughs.

He’s a sharp dresser, and credits his wife as his stylist. “She says, ‘Oh no, use this tie, this pocket square … Oh, you need those shoes to go with that.’ She has a great eye for fashion, it’s really a great thing.” He is a public speaker, a criminal justice reform advocate (he sits on the board of The Innocence Project), a poet and now a published author. In 2016, President Barack Obama honoured him with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

And what does la dolce vita, the good life, mean to Salaam? He sees the beauty of just being alive. “To be able to live fully, be appreciative, be thankful, be humble, be human, keep your humanity, never allow the system to turn you into a monster, but do everything with grace and mercy, and always become more better and less bitter,” he says.

In a telephone interview, Yusef Salaam graciously spoke to Dolce about everything from defining hope and justice to women and children in his life — and standing on the shoulders of his ancestors to choose better, brighter, stronger and wiser.

Q: How do you define justice?

A: My definition of justice has a lot to do with making sure people are being treated fairly from the start. There’s a lot of injustice that goes on in the world, and a lot of it is man’s inhumanity to man. When you think about my case, for example, you really get the opportunity to kind of understand the broad view, just because time has gone by, how people built their careers off our backs.

Had justice prevailed in the Central Park jogger case from the beginning, we would have never gone to jail, we would have never been victimized and criminalized in a system that says that we are innocent until proven guilty. We were seen as guilty having to prove ourselves innocent, specifically because of how Black and Brown bodies have been socialized in this country.

It’s not like the socialization happens, and everyone who’s here immigrated to this country willingly. We were imported. Those of us who know the true history can understand it, perhaps had done genealogy work to retrace their steps and family steps. We were taken against our will from places that we were in and turned into cattle slaves, and then our memory of home was completely erased. I remember a quote by Dr. James Baldwin, who said, “To be African American is to be African without memory and American without privilege.”

“You May Wonder How An Innocent Man Keeps Hope Alive Behind Bars. Yusef Salaam Found Prayer To Be His Greatest Inspiration”

Q: How do you define hope?

A: My definition of hope is never giving up on the true purpose of who you are. And what I mean by that is, when we go and we understand that when our mothers and fathers got together, we were all one of over 400 million options, each and every one of us, every human being on the planet, and we made it, right? And the fact that we made it means that we were born on purpose, and we were born with a purpose. And I think that the greatest hope that we can have is to find the purpose, that we were born, and as Dr. King said, to live it as if God himself called us to do it at that very moment of time.

There’s so much happiness, and there’s so much pride, and there’s so much good vibrations that happen when you live in your purpose. And that’s the most hopeful that you can be, because as soon as you give up hope, all of the darkness around you begins to overcome the light that is trying to be buried by the darkness. But when you have tremendous hope in yourself, in your body, in your community and in your life, you begin to turn your light up, you live on purpose, you don’t ask permission to do what it is that God gave you the right to do, and to be, which is human, and it’s a really liberating thing.

Q: In your book, you explain how you are often on high alert. How do you relax, or do you ever have a chance to put your guard down?

A: Never. You know, being in a situation where you were run over by the cycles of justice for one, in a country that sees Black and Brown bodies as crimes, and, therefore, people who look like me don’t get the opportunity to live as full a life as they can or want to. Even if they’re living life now, oftentimes the life that they’ve been living has been a life where they’ve been walking on eggshells, and what kind of life is that to live? What kind of hope is that in the future, as opposed to being given the opportunity to live as full a life as you can and should be living?

“You And I Were Born On Purpose And For A Purpose” – Better, Not Bitter

I think being aware of the hyper-vigilance that you now have to live in and move in and thrive in also gives light to what Dr. James Baldwin said when he said something to the effect of, “The victim who can articulate the situation of the victim has ceased to be the victim; he or she has become a threat.” And so, we’re trying to figure out how to set as many people free as possible, and a lot of it is to understand the space and the place that you’re in, to know who you are, to know where you are, why you are, what you are and, most importantly, how you are. Because in a state that you find yourself in terms of hyper-vigilance or the margins of life, quite often you also find yourself in great mental challenges, so the mental health in those communities is very real and very challenging, and the grace that’s given to people who are going through that kind of crisis is not really afforded to people with Black and Brown skin. They’re told to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, and Dr. King said something very interesting, he said that is one of the most cruel things you can say to a bootless man.

Q: You dress impeccably and you mentioned that you designed some of your clothes even when you were younger. Has fashion always played a role in your life?

A: It always has. My wife is actually my stylist. She has a great eye for fashion; it’s really a great thing. A friend of mine, Jimmie Gardner, who did 27 years for a crime he didn’t commit, I remember he said one day, “Thank God I don’t look like what I went through.” What a beautiful statement.

So, when you see us, you get the opportunity to see people who still have life in them, to see people who still can smile and appreciate things, as opposed to people who have become bitter. So, even in the title of my book, Better, Not Bitter, there’s an opportunity there. There’s an opportunity because of what Dr. Maya Angelou encouraged us to become: alchemists in our lives. She said, “You should be angry. You must not be bitter.” She said bitterness is like a cancer, it eats upon the hosts. It doesn’t do anything to the object of its displeasure. In the alchemy, she teaches us to use that anger — you dance it, you march it, you vote it, you do everything about it, she said, and then you talk it, never stop talking it.

I found that when I grace stages, it is a greater visual picture and representation to be standing there looking like I was one of the characters in the Bible, Shadrach, Meshach or Abednego, having gone through the fire, and not even smelling like smoke.

I love being able to represent not only myself, but also people who have been run over by life in that way, because it gives them the opportunity, not necessarily for the system to see them differently, but for them to see themselves differently. When you look at yourself in the mirror, you feel better when you clean up, and I think that’s the thing that we should all take a lesson from: it has nothing to do with the oppressor, it has everything to do with your own mind and your own mentality.

Q: Can you tell us how poetry helped you in prison?

I’ll Meet You in Between Venus and Mars

In between Venus and Mars

Is the center of our attraction

Of those connected to the stars

Hardly a fraction

It behooves man to work for the day

When this will all end

Life is mortal, so follow the ways of those Heaven sent

Awaken and receive that which will give you life

Or remain horizontal and never begin the flight

For the solution, I’ll descend from amongst the stars

And I’ll meet you in between Venus and Mars.

— Yusef Salaam

A: Just the thought of that, just the revisiting of that poem, here I am in prison, I’m in Clinton Dannemora [Correctional Facility] talking about “I’ll descend from amongst the stars.” I would never have imagined that I would be in a place or space in the world where I would be celebrated, because we were victimized and we were turned into the pariahs, into the scum of the earth and, so, to even write those words to encourage me, one day you’re going to make it, one day you’re going to make it big … and meet people on Earth in between Venus and Mars, and share your story, share your grace with them.

Q: A lot of inspiration comes from outside stimulation — nature, travel, along those lines. Where did you find your inspiration when you weren’t super-stimulated?

A: I’ve always found the greatest inspiration in prayer. Prayer is something that I have to do at least five times a day. The more awake you are in that process, the more that process reveals itself to you. And so, I’ve always been really appreciative whenever I tapped back into the sacredness of life, to be able to plug in for all creation, and it’s a really powerful thing because you find, even in your own heartbeat, you can be inspired.

Q: You spoke about your platforms and how that’s kind of a silver lining to the experience, because you’re able to help other people now and inspire other people, of course, and I was wondering if you could speak on The Innocence Project and how your experience has been able to help others who have gone through a similar experience?

A: Yes, so I sit on the board of The Innocence Project with other great members of the The Innocence Project and I tell you, these are graces afforded to you because you are able to use the opportunity that you have grown through. And I’m going to use that word intentionally, that you have “grown” through, you’ve been able to use the opportunities to really shed more light on things.

I think that when people know that I’m on the board of The Innocence Project, there’s a great deal of aspiration and inspiration that happens with that, and it shows where you can go and also what you do when you get there. And so, some of the most egregious realities that I’ve been experiencing have been as a result of The Innocence Project, being able to free people through DNA evidence. And this wasn’t, “Oh, there was a blunder, and the courts and something happened and made a mistake.” This is, “These individuals were innocent, and you knew it all along.” And maybe the science wasn’t there when they were arrested, but there “weren’ts” were, the evidence of what was in the case was. Remember in the Central Park jogger’s case? They said that Raymond Santana and Kevin Richardson, after they were picked up that night, they said that Kevin had gotten a scratch on his face because he was struggling with the jogger. There was no skin underneath his fingernails. They said that this woman had been brutally raped and left for dead. Had this been true, then that would’ve meant that Raymond Santana and Kevin Richardson, the first of the five of us to be arrested, would’ve had evidence on them, blood at least from the victim, after doing such a heinous thing.

You can’t escape a splatter had you bludgeoned someone. And when you think about what the real perpetrator said and how he said it, and what he did, you know one of the most interesting things is that when he was leaving Central Park, the police officer saw him, and they came up to him in their car and shined their light on him, and they shined their light on his face, and they asked him if he had seen any young people in Central Park. And, of course, he said no. He had just finished raping the Central Park jogger; he was walking out of the park with her headphones on his head listening to her music. He said, “No, I hadn’t seen anything.” And they said, “Well, listen, go on. It’s a little crazy in the park tonight.” He said, out of his own mouth, “Had they shone their light on me from the waist down, they would’ve seen that I was bloody from the waist down.” Now he’s out there, left to commit more crimes because the system believes that they got it right, and they got it so wrong. And one of his last victims was a young pregnant Latino woman, who I imagine, if we can kind of try to recreate this horrific crime scene, that he comes into her home, and she thinks the worst: I’m about to be violated. She’s pregnant, she’s there with her two small children. She pleads with the assailant, “Can you please just let me put my two children in the next room?” He allows her to do so, then prepares himself. And she comes out and she’s probably thinking, This is going to be bad, but I’m going to survive. His modus operandi was at that point to kill everyone whom he harms. He used to say when he gave his victims a choice after he did the deed, “Your eyes or your life.” And if you said to him you could live without your eyes, he would cut them out, so that you could not identify him in the court of law. But if you could not live without your eyes, he would kill you, almost certainly try to. And in this particular instance, he stabbed her to death. The people, the residents in the building, her neighbours, hearing her pleads, hearing her cry, came out of their homes and they sat on him. And they did a citizen’s arrest and held him until the police came. That’s how he got caught. He didn’t get caught because of the police work, he got caught because of the great work of the residents in the building. He was what people knew in that neighbourhood as the “East Side Rapist” and the “East Side Slasher,” because if you fight him off, you might get caught. But if you didn’t fight him off, you might get raped, harmed, now murdered.

Q: You described your situation as people looking at you as if you were the scum of the earth, which is horrible. So how do you deal with that transition mentally, from that point to, let’s say, a higher point that you’re experiencing now, and the fact that you never changed, and the fact that it was never your fault?

A: I love that question. You know, in Islam … in the adhan [call to prayer] played in various Muslim communities, you hear “Allahu Akbar.” What that saying means is that God is the greatest, or God is greater than anything you can imagine. And so, here you are, you’re walking throughout your day and all of a sudden you hear the adhan and it really is calling you because, remember, God is greater than what you’re doing, so if you just pause for a moment, I mean prayer can be as short as five minutes, if you just pause for a moment, you reactivate the thankfulness that you should always be about. And by being thankful and remaining in a state of thankfulness, remaining in a state of humbleness and humility, you really give yourself the greatest opportunity to be giving more and more and more.

As soon as you say to yourself, “I got this because I survived,” I’m saying that there’s a certain truth to that, but in that truth is also that God is the footprints that you did not see, right? I’m talking about the poem “Footprints,” because there’s always a question when you’re going through so-called hell, they say you got to keep going to get out of it. You know when life knocks you down, as my good friend Les Brown says, try to land on your back, because if you can look up, you can get up.

In this particular case, we fell on our face, and so I wasn’t able to hear the words of the great philosopher Cardi B yet, who said, “Knock me down nine times, and I’ll get up 10,” but that’s what life is about. And I think that the more thankful you are, that God is the orchestrator of all of this, the more you see the hand of God in it, the more God raises your light in the world and allows it to be guidance for others. But then, the more humble you have to be, and the more thankful you have to be, and the more humble you have to be, and the more thankful you have to be. And there’s a certain level of happiness that comes from that, because when you let go, as the church says, when you let go and let God — oh, man.

Q: Can you share the story about meeting your wife in Starbucks? How has she has helped you heal?

A: There was this moment, and this was the most truest thing that I have ever felt, there was this moment when I was in my mother’s office, and there was this feeling that I should take the trash out. And then I just had this overwhelming feeling to go for this walk, aimlessly walking downtown and I walk into Starbucks (at that point it was the only Starbucks in Harlem). It was the one that Magic Johnson had brought to Harlem; it was the coolest thing when he brought it there. I actually worked at that Starbucks as well.

Here I am standing in Starbucks. And I’m realizing I didn’t tell anybody back at the office that I was going to Starbucks; they probably want something. And I’m calling them, asking, “Hey, what do you guys want? I’m here at Starbucks, what do you guys want?” She’s in front of me and she doesn’t say anything yet, but she’s watching me. And she told me that later on she was saying, “Who comes to Starbucks and doesn’t know what they want?”

Then all of a sudden, she caught my eye, and I walked up to her and she said, “Can you believe it?” I didn’t know what I was going to say. I didn’t have any kind of cool points or how to talk to women or anything like that, but I walked over there and her energy was just exuding out of her and she said, “Could you believe it? There’s no soy milk.” And I’m not even aware that she said that there’s no soy milk. I see her mouth moving, and I remember hearing myself say, “Are you a model?” and she’s looking at me like, “A model? I’m 5-4. How could I be a model?” But the way that she looked and the expression, it was just graceful.

When I got a chance to revisit it in my book, it was more profound than what I had imagined and understood it to be even at that time. Because when I talk about it in my book, I want people to understand that you have to always be listening to the grace of God, you have to listen to your gut, when your gut tells you to move, you have to understand that when you let go and let God, magic happens.

In this case, here we are 14 years later, with a beautiful blended family. When we met each other, we had three children each. She had two boys and a girl, and I had three girls, and as we began to grow our family we had another girl, and then another girl. And then, we had two more children. One was a girl, and then, on my 42nd birthday … my first son was born to me, so he is a Junior in the truest fashion. His name is Yusef Salaam. He has a different middle name, but hopefully he’ll have all of the blessings and none of the hardship, none of the heartache.

“The Sweet Life For Me Is Finding The Beauty In The Rubble, Finding The Hand Of God In It All”

Q: What would you consider to be la dolce vita, the sweet life?

A: I have a really funny story. It’s a sad story, but it’s a cool story at the same time. So, at one point in my prison time, I was in prison with Kevin Richardson. And Kevin Richardson is, of course, one of the members of the Exonerated Five, and we were in the same prison for a few years together, not living in the same housing unit at the time, but we would see each other sometimes in the mess hall. And I would raise my milk carton, the same milk cartons that you would find in elementary schools, high schools and junior highs, things like that. I would raise my milk carton, and I would say, “Yo, Kev, to the good life.”

The sweet life for me is finding the beauty in the rubble, is finding the hand of God in it all. When I look at the Central Park jogger case, lately I’ve been describing it as a love story between God and his people. I’ve said that it’s a story where God has used this case in particular to put the whole system in America on trial. It’s a story where people can be brought low only to rise, because the truth can never stay buried, and it’s a story of a people buried alive and forgotten, but the system forgot we were seeds. So, instead of a social death, we’ve been able to emerge like the phoenix from the ashes, because if they built a fire to consume us, they forgot the owner of the heat.

This is a beautiful struggle when you can reorient your idea and understanding of what it is that you’re going through, because instead of you going through something, quite often you’re going to grow through something, but it has a lot to do with your attitude.

And so for me, la dolce vita is to be able to live full, be appreciative, be thankful, be humble, be human, keep your humanity, never allow for the system to turn you into a monster, but do everything with grace and mercy, and always become more better and less bitter.

www.yusefspeaks.com

dr.yusefsalaam

Interview by Estelle Zentil