The Year of Barry Avrich

With a memoir on the way, a shot at producing the Canadian Screen Awards and directing three films for the Stratford Festival, director Barry Avrich reflects on a life in the foreground.

Two-thousand-sixteen, in a lot of ways, is going to be one hell of a year for Barry Avrich. This is what he tells me. He thinks it’s an interesting thread for my story, the story I’m writing on him for the Fall issue of Dolce, “and I’ll tell you why,” he says.

He sits business-casual in a crisp white dress shirt and blue jeans, remnants of the photo shoot that just wrapped in his midtown Toronto home. To his right hangs a trio of three sheets — old Broadway posters from New York’s Lincoln Center — illustrated and signed by graphic artist James McMullen. Backyard trees obscure the light of the afternoon sun, casting the unlit living room in a sinking darkness, as if theatre house lights were slowly dimming. A faint glow creeps through the floor-to-ceiling windows and lines his Billy Crystal hair and Richard Gere eyes.

For one, he continues, he’s directing three films of Shakespeare productions, major 12-camera shoots that will be the eighth, ninth and tenth films for the Stratford Festival. Secondly, he’ll be producing the Canadian Screen Awards in March of next year, adding the Avrich flair to Canada’s answer to the Golden Globes. And thirdly, he has a book on the way. “It’s my fourth book, but it’s my first memoir — and last,” he says.

Barry Avrich tells me all this because he’s both a savvy businessman and a self-aware director. This September marks his 30th year as a professional in both film and advertising. Over that time he’s established himself as a force of Canadian advertising — he’s a partner at BT/A Advertising, representing clients such as the Toronto International Film Festival and the AGO, and won the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of The Year Award in 2009 for his efforts — and as a workhorse documentary director. Because he’s straddled these two worlds, he understands that whether you’re releasing a film or a product, you want, and need, ubiquity — that omnipresence that flows into our collective consciousness and generates the necessary attention for a successful launch. Or, more bluntly: “You want buzz.”

He switches to full Storyteller Mode as he recalls a conversation with Robert Evans, the former head of Paramount Pictures. Evans, Avrich explains, is the subject of the documentary The Kid Stays in the Picture, “one of the greatest documentaries ever.” You need to have seen the film to understand who he is, he continues, because he’s famous, has a butler and whatnot, and lies in a mink-lined bed all day in pyjamas. Avrich drops his voice a few octaves and slides into a rolling, nasally accent. “‘Ahhh, Barry,’” he says, impersonating the producer that green-lit such classics as The Godfather and Love Boat, “‘you have to decide whether you want to be the background or the foreground.’”

And this is what Avrich understands, more so than most. We’re all brands, and that personal product needs to be marketed just like anything else. So here’s Barry Avrich, doing what he’s been so good at for three decades: creating buzz for the product of Barry Avrich.

Over the past 15 years, Avrich has built a reputation as one of Canada’s premier documentary filmmakers, doing so with an entrepreneurial drive that few people possess. He runs his own production company, Melbar Entertainment Group, and he has written, produced and directed much if not all of the nearly 30 works for both television and the big screen that he’s credited for. But he’s made his name chronicling the lives of titans of the entertainment industry. In 2012’s Show Stopper, he told of the rise and fall of Garth Drabinsky, the Canadian producer and entrepreneur who founded Cineplex Odeon and Livent. In 2011, he tackled the volcanic Harvey Weinstein in Unauthorized. But arguably his best-known work is The Last Mogul, a look at the monumental presence of one of Hollywood’s most influential figures, Lew Wasserman.

“I love telling their stories because I’m fascinated with power,” Avrich says about his draw to these movie magnates. “I don’t want power. I don’t have power. But I’m fascinated at the risks and the sacrifices that the people in my films take. Some of them lose it all. Some of them didn’t have to lose it. Some of them end up with nothing. Some of them have gone to jail. Fascinating. Fascinating to me.”

Through his various works, he’s collaborated with or interviewed the who’s who of entertainment. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones, Larry King, Larry David, Bono, Martin Scorsese, Jerry Seinfeld, Matt Damon and former president Jimmy Carter are just a few of the names attached to his projects — and he’s got a story for them all.

When he interviewed Richards and Jagger for an episode of Life and Times on concert promoter Michael Cohl, for example, he remembers the contrasting personalities of the bandmates. “I interviewed Mick first and then Keith and they were so diametrically opposed in their openness and their style,” Avrich says. “Keith’s the guy I’d love to hang with. Mick, I could do a business deal with.” He even recounts a story about interviewing comedian and Full House star Bob Saget that’s far too graphic to share here.

His talent for film production is an obvious extension of his storytelling prowess. His father, Irving, could spin a tale or crack a joke with the best of them, and there were plenty of comedy albums present in the Avrich household. It all helped him learn the rhythm and cadence of an engrossing story. And there’s no question: Avrich is a natural raconteur. “I love telling stories. That’s why I chose the art form of documentary,” he says. But, he adds, “also to selfishly meet interesting people.”

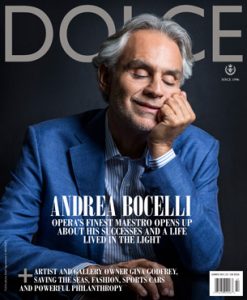

Take his documentary on Vanity Fair society and crime columnist Dominick Dunne, aptly titled Guilty Pleasure. The reason he made the film was simple: “I wanted to meet him.” Last Sunday, even, after an Andrea Bocelli concert at the Hollywood Bowl, Avrich made his way backstage simply to speak with the Italian tenor, because, well, he wanted to.

Many of these famous individuals have become “life mentors” for Avrich. His dad passed away over two decades ago and ever since he’s surrounded himself with father figures to fill the shoes left behind. He’s collected their words of wisdom to shape his relentless, unapologetic approach to life. Longtime friend and co-founder of TIFF Dusty Cohl always told him, “You can’t execute a plan without a good accomplice.” The legendary American record producer and Grammy hoarder Quincy Jones explained the secret to his life was to “live, love, laugh and give back.” When Avrich confided in Jones that a former friend was causing negativity in his life, Jones washed away the anxiety with one illuminating line: “You can’t have a great picture without the negative.”

Avrich’s childhood home in Montreal was never one of wealth or fancy, but it was one of culture. His parents would always have art strewn about — a sculpture here, an oil painting there. Nothing expensive or of great prominence, but it instilled an appreciation for creativity. His Toronto home too is adorned with a number of attention-grabbing works, including an electric portrait of Andy Warhol by a Japanese artist using a thousand Bic pens. “I just saw it and had to have it,” he says of the work. In order for a piece to make it to his collection it needs to be emotional, but not depressing. “I’m not going to be turned on by Jackson Pollock,” he explains. “I appreciate the art, I appreciate the scale and I appreciate the power, but it’s not emotive to me. A piece has to tell a story and be emotional for me.”

Avrich’s mother used to take him to art galleries as a child, in Montreal or New York — they’d often seen exhibitions at MoMA or the Guggenheim — and they share a similar taste, as does his wife, Melissa Manly. About the only person that doesn’t like his choice in art is his daughter, Sloan. When he brought home a nude from London, England, his daughter was aghast. “She goes, ‘I wasn’t consulted about that piece.’ I said, ‘You’re 11. Why would you be consulted about it?’ And she said, ‘Well, I’ve got friends that come here. That needs to be moved to the basement,’” Avrich remembers. So he told her that when he’s dead she could sell his collection, if she wants. “And you know what she said? ‘Immediately.’”

Every year Avrich’s parents would also take the family to the Stratford Festival in the summer and head to New York for the Broadway season in the fall. The first production he ever attended in the Big Apple was Michael Bennett’s A Chorus Line, “and that was life changing,” he says. He became fascinated by the industry and at eight years old began reading Variety. “My parents both opened up my eyes certainly to the entertainment industry, Broadway and then what it is to have a good seat,” he says. “I will always have a good seat if I go to the theatre. I don’t care what it costs.”

In 1980, Avrich moved to Toronto to study film at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute and the University of Toronto. His uncle advised him to consider a career in advertising, as he quipped he would likely starve working in film in Canada. “‘You will end up working for the National Film Board and you will end up making films about the gestation period of a beaver.’ That’s what he said to me, at the age of nine. I’ll never forget it,” says Avrich.

In 1985, Avrich began his marketing career at Borden Advertising. But his passion for film never subsided. He made the shorts The King of Yorkville in 1985 and eventually The Madness of Method in 1996, which took home a gold medal at the Bilbao International Festival of Documentary and Short Films.

Avrich would create Melbar Entertainment Group in 1998 to produce his films, and, while still juggling his marketing career, began pumping out movies at a consistent rate. It was in 2005 when he made his biggest splash with The Last Mogul. The film focuses on the rise of Lew Wasserman, from the streets of Cleveland to the heights of power in the centre of the movie universe. He was a man both prevailing and private — one who never wanted his life immortalized on film.

“I wanted to make the film on Lew Wasserman primarily because I met him at a party in Los Angeles and he told me that it would never be done,” Avrich recalls. “He put his hand on my shoulder with his thumb in my neck and said, ‘The film won’t be made, whether I’m alive or dead.’”

It wasn’t a bluff either. Wasserman passed away in 2002, but Casey Wasserman, Lew’s grandson, also a major player in Hollywood today, did everything to keep the film from seeing the light of day. Avrich explains that Casey put the word out, telling individuals that would be valuable to the story not to participate. Avrich received threatening calls telling him not to make the biopic, and during production he would move from hotel room to hotel room, worried about protecting the film stock.

But despite those efforts, Avrich would get key interviews and the film would be made. When it was released in 2005, it was received favourably. The Hollywood Reporter even called it Oscar worthy. This past April, The Last Mogul received a 10-year retrospective at the Hot Docs film festival, where Cheryl Boone Isaacs, the first African-American president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, introduced the film.

“Barry’s got a nose for a good story, in his films and in his personal life,” says Chris McDonald, president of Hot Docs. McDonald explains that good films boil down to storytelling and that Avrich explores his subjects with a journalistic depth, loaded with interviews and history, but does so in an approachable way. “He makes these stories accessible and interesting and as entertaining as possible,” he adds. “They’re not didactic, they’re not plodding, they move along at a really nice pace, and they really help to illustrate in a creative way these fascinating lives.”

Avrich has been a board member of Hot Docs for the past half-decade and has offered his expertise in shaping the organization’s marketing and communications strategies to great success. As McDonald adds: “I have no idea how he runs a successful business, he makes a feature-length film every year and he puts in a tremendous number of volunteer hours. It’s kind of exhausting to think about.”

While Avrich does donate his time liberally — he was also a board member of both the Stratford Festival and TIFF for a number of years — one of his proudest moments was bringing a theatre to the Hospital for Sick Children. While visiting a friend in a hospital in 2006, Avrich, who has such a dislike for hospitals he won’t even drive down University Avenue, walked by a room where he saw a child fumbling with a portable DVD player. “I thought to myself how horrible it is that if you’re in a hospital as a child you can’t escape,” he says.

He called the Hospital for Sick Children and explained that he had an idea to pitch. But in true showmanship fashion, he told them they only had 48 hours to say “yes” or “no.” Avrich is no stranger to bureaucracy and knew if he didn’t get things going fast his idea would likely be bogged down in red tape and simply not happen — hence the 48-hour deadline. His idea was simple: build a theatre in the hospital so the children, many with life-threatening illnesses, could have some diversion from their plight. The hospital liked the idea. Avrich started making calls and knocking on doors to amass the $1 million needed to construct it. Two of the biggest donors were founder of Cadillac Fairview John Daniels and his wife Myrna, and when the theatre opened a year later, it was named the Daniels Hollywood Theatre in their honour.

“Often you have great ideas that just don’t get executed, and I was thrilled that I got it done. I was thrilled that I was able to offer a bit of a sanctuary, an oasis for these kids to disappear from their own illness,” says Avrich. “Other than my daughter, it was easily the proudest achievement in my life.”

Much of these stories will fill the pages of his forthcoming memoir, which he describes as his “uncensored life amongst moguls, monsters and madmen.” One of the major reasons for writing the book, he says, was to send the message that success is achievable by anybody: “It doesn’t matter what your education is — I didn’t have a fancy education, I was not an academic, I was not a scholastic genius — you can do anything.” Avrich takes an articulate stroll down memory lane and stops at the immortal words of his father: “Get out into life and don’t blend in,” he says. “Don’t blend,” he repeats to solidify their gravity. “Great words.”

The book, though, was difficult to write. While he’s met so many interesting people and lived what he feels is a fantastic life, he’s painfully insecure. He thinks readers will love all the show business anecdotes and “crazy name-dropping.” But will they care about his story? “Are they going to care about my childhood? Are they going to care about the fact that my parents introduced me to culture? I don’t know,” he says. “So I’m completely panicked about it.”

The problem, he feels, is the Canadian attitude toward success. “It’s always the glass half empty, and it shouldn’t be,” he says. Canadians simply don’t celebrate success the way Avrich believes they should. It’s a phenomenon that he feels his friend and Toronto Star theatre critic Richard Ouzounian got right when he applied the “tall poppy syndrome” label. “If you grow a little too tall they cut your head off,” says Avrich. When this story comes out, he knows there are those who will simply dismiss it on the grounds that there’s nothing special about him that warrants such coverage. As a Broadway producer once told him: “‘Kid, the only way you can succeed in Canada is to leave and bring back your press clippings in a suitcase.’ And that’s what it is.”

Avrich feels he’s often painted with the “too commercial” brush. Canadian broadcasters generally look for social impact films, but Avrich isn’t interested in making those. “There are lots of filmmakers making social impact films. I’m not going to make a film about an oil spill. It’s vitally important, but that’s not the film I want to make,” he says.

I suggest that, judging by his past work, Conrad Black would make for a great subject for an Avrich film. “Conrad Black would love for me to make a documentary film about him, but I’m not going to do it,” he says. He doesn’t believe there’s much interest in Black’s story outside of Canada, and besides, “the only way to do it is for him to participate. You have to sit down and have that great interview with him,” he says. “I don’t think he would allow me to do it unless he had some kind of final cut. I’m not doing that.”

If you’re wondering about Avrich’s secret for living a life that seems to require 25 hours in a day, it’s all about rest — or lack thereof. “I sleep four hours a night,” he explains. Ever since his father’s passing, Avrich has had a fear that he would be dead by 50. “I was convinced of it. Convinced of it!” he says. So he’s done everything possible to maximize every waking moment. “My feeling was that if I was, god forbid, on an airplane going down, if I was told I had a terminal disease, great, no problem. I’ve done everything that I wanted to do,” he says. Now that he’s 52 and passed that threshold, he sees every year as a bonus, “but I’m still cramming everything in.”

And “cramming” is an understatement. On top of the memoir and producing the Canadian Screen Awards and his new short, The Man Who Shot Hollywood, making its world premiere at this year’s TIFF, he’ll be directing three films of Shakespeare plays for Stratford Festival HD. Last year, he produced King Lear and produced and directed King John and Antony and Cleopatra for Stratford — experiences he equates to going 100 miles per hour in a Ferrari without any breaks. This year they’re aiming to do Hamlet, The Taming of the Shrew and The Adventures of Pericles. Stratford Festival’s artistic director Antoni Cimolino explains that while they did films like these in the past, Avrich has brought an expertise and a “can-do attitude” that’s made it possible with more regularity.

As the afternoon sun steals further away, Avrich turns sentimental. After telling the story of sitting onstage with his daughter after her screening of her short film, Red Alert, at last year’s TIFF, Avrich speaks of finding quality time with those he loves. “My daughter has become my lighthouse,” he says. Even if one of his films gets a terrible review, he knows he can always come home to that “unconditional critic” in his life that loves him no matter what. “And that’s big,” he says. “She’s my Academy Award.”

That’s why, when it comes to his dolce vita, Avrich has a deep appreciation for the quiet times. It could be on a beach or on a plane, anywhere he can be alone with his wife and daughter and not have to worry about a phone call or the 400 emails he gets daily. “It is life uninterrupted with my wife and daughter. That’s my dolce vita. It rarely happens, but I like that,” he says.

So while Avrich’s life is teeming with star-studded experiences and 2016 is set to be a year to remember, it also seems that, every now and then, tuning out the buzz and spending a little time in the background isn’t such a bad thing.

The Reel Deal

Over his 30-year career, Avrich has directed nearly 30 works for television and the big screen. Here’s a look at some of those titles.

The Man Who Shot Hollywood (2016)

Antony and Cleopatra (2015)

King John (2015)

In Studio: Up Close and Personal (2014)

Filthy Gorgeous: The Bob Guccione Story (2013)

Quality Balls: The David Steinberg Story (2013)

Show Stopper: The Theatrical Life of Garth Drabinsky (2012)

Unauthorized: The Harvey Weinstein Project (2011)

An Unlikely Obsession (2011)

Jackie Mason: The Ultimate Jew (2008)

The Citizen Cohl: Untold Story (2008)

Maurice Richard: The Legend, the Story, the Movie (2006)

The Last Mogul (2005)

Guilty Pleasure: The Dominick Dunne Story (2002)

Glitter Palace (2002)

No Comment