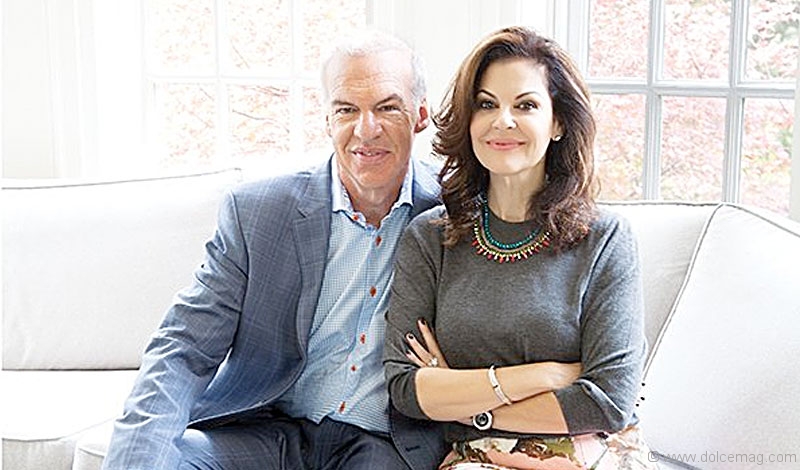

Mark Daniels & Andrea Weissman-Daniels: A Single Spark

Falling leaves flutter past the windows of Mark Daniels and Andrea Weissman-Daniels’ York Mills home, landing wherever sporadic, indiscriminate gusts deem fit. They scatter in the autumn wind, coming from who knows where, their final destination equally as vague. Undoubtedly, a forlorn existence, as it is for many children without homes, a reality with which Daniels and Weissman-Daniels empathize. They’ve seen it before, witnessed the loneliness and unrest, the resulting wariness and withdrawal in the eyes of children within the child welfare system, those lacking a permanent home and a “forever family.” But it’s a feeling this couple endeavours to soothe; one they know can be diluted. All it takes is a single spark.

Inside the Daniels’ home there is a cacophony of activity. Daniels and Weissman-Daniels are being dressed to the nines as stylists, makeup artists and the like prep them for camera. Weissman-Daniels, in a billowy black-and-white gown, remains as poised as a veteran actress — which she is — and Daniels, a partner at Daniels Financial Corporation, orchestrates the tunes while recounting, with the flair of a seasoned raconteur, a tale of literally bumping into renowned jazz guitarist Pat Metheny in New York City. But such flurry, such glitz and glam, isn’t the everyday for this pair. “Normally I’d be dressed like you,” Daniels says of my jeans and dress shirt. It’s all out of necessity, a means to an end, Weissman-Daniels later echoes. The world of philanthropy is highly competitive. Many organizations clamour for whatever slice of the charitable pie they can get. You need to dress your cause up in order to get it noticed and to meet its goals. The formal attire is something this couple can easily bear.

This husband-and-wife team is the face behind the Ignite the Spark Fund. An arm of the Children’s Aid Foundation, this initiative aims to improve the lives of children within the child welfare system through “enrichment activities” — sports, arts, recreation, cultural activities, whatever the child’s interest — that they otherwise would not experience. It may seem like an inconsequential matter, games and art, but these activities cultivate the skills and confidence these children need. In the current system, however, the money just isn’t there. “There’s a huge gap … in funding for the kind of empowerment and enrichment activities that develop their identity, self-esteem, confidence, skills, all kinds of wonderful aspects of a whole human being,” Weissman-Daniels says. “Without them, they become victimized by their histories.”

These are not just a handful of children who have been handed the short end of life’s stick, either. According to the Children’s Aid Foundation, one in 25 Canadian children is considered “at risk.” More than 300,000 children receive some form of child welfare service and, of that number, approximately 76,000 are “Crown wards” (children living in foster care or other residential programs). Each year, 30,000 children in the Canadian welfare system wait for permanent adoption. However, less than 9 per cent are adopted annually. Only 30 per cent will graduate high school (the national average is 88 per cent), and studies show more than 40 per cent of homeless youths were at one time involved in child welfare services. These kids often languish, endure abuse or neglectful environments and suffer from deep-seated emotional issues that may not receive proper attention. And what’s worse: it all flies under our collective radar. It wasn’t until 2011, in fact, that the national census counted the number of children living in foster care (there were close to 48,000). “It’s not that a lot of people are wilfully neglectful,” says Daniels, who also notes that many, many foster homes do great work and give children shelter and care where they otherwise would have none. “This just doesn’t enter into their daily lives.”

“These are the leaders of tomorrow,” adds Weissman-Daniels. “I appreciate they’re a percentage of the population, but they are a percentage of the population whose potential is not being realized. So they’re either going to be part of the solution or they’re going to be part of the problem.”

A number of these children will be tossed from home to home — perhaps taken from their parents and put into a foster home, back to their parents, then back to a new foster home; new schools, new everything — constantly lacking stability and continuity. The process can leave these children insecure, jaded and distrustful, as they must wade through emotions and issues most other children will never face. “They have really limited trust of any adult,” Daniels says, “because every adult they’ve ever met has given them a hard time. They’re being pulled from place to place to place, and by the time they get adopted they don’t trust any adult.”

It was something Daniels and Weissman-Daniels had to address when they adopted. The pair didn’t meet until later in life. Weissman-Daniels had worked as a choreographer and then an actress, starring in television shows in L.A. and Vancouver, before working as a film producer for Livent and eventually Alliance Atlantis. Daniels was busy building a real estate development company with his brothers and embarking on globetrotting ventures that would see him journey to Russia at the end of the Cold War, dealing with the KGB and helping secure one of the first business deals between a North American enterprise and the former Soviet Union. By the time they met and married nine years ago they were past their mid-40s — having a child of their own wasn’t in the cards. “Adoption was the natural next step,” says Daniels.

Their daughter, who was 8 at the time of adoption, struggled to socialize and integrate into her new school. “She

was lovely. She was mischievous. She was the devil. She was cute. She was fun. She was full of energy,” Daniels recalls. “But, it took a long time to get settled, to realize this was going to be her home, and that she was safe and that she could trust us. Trust was a huge issue. Huge.” Weissman-Daniels points out a candid photo of their daughter from the early days of the adoption hanging on her office wall. She describes the wildness, the caginess, the pain in that little girl’s eyes. They realized, in those early days, that she had never had the opportunity to find an activity she enjoyed, a passion she could embrace. They put her in soccer, ballet, figure skating, swimming, but nothing seemed to click. They decided to try horseback riding, and the response was immediate. “It was just like fireworks went off,” says Daniels.

She immersed herself in the world of riding, learning about horses, their types, temperaments and how to care for them, and all about the equipment used when riding. As her riding skills improved, she began entering competitions and, surprisingly enough, winning. “It gave her huge amounts of confidence,” Daniels says. As a percussionist and Canada’s oldest competitive trampoline gymnast, Daniels understands the value of those stepping stones, that ability to build on past successes and gradually progress. “We wanted to use the athleticism as a jumping-off point,” he says. “You learn this and then you can jump to that and then you can jump to the next.” The confidence gave her the emotional strength she was missing, a sense of self and purpose, and taught her about building symbiotic relationships with others.

Weissman-Daniels pulls out a more recent photo of her daughter, noting the peace and optimism she now exudes. Weissman-Daniels knows the power of riding, of finding that passion, as a catalyst for new beginnings: “It was the beginning of the rest of her life.”It’s this gift the couple hopes to share with other children through the Ignite the Spark Fund. Over the four years the Fund has been in operation, it has already raised nearly $450,000 and attracted the community’s attention with its star-studded Spark Galas. These galas have honoured luminaries — like figure-skating phenomenon Patrick Chan, Dragons’ Den Arlene Dickinson and The Guess Who alumni Randy Bachman — who demonstrate what happens when potential is nurtured. “Nurture the passion,” says Daniels. “Continue to nurture it, because you’ll be amazed how much it brings a kid.” These funds have provided 85 kids with access to the activities of their choice, covering enrolment, equipment, examination and transportation fees.

The commitment to each child is long term (a minimum of three years) — Weissman-Daniels feels it’s terrible to allow children to experience a fulfilling activity once or twice and then take it away, “again, another disappointment” — and supports youth up to 21 years of age. In the current system, once children turn 18 they “age out” and are no longer supported by government funding. In a time when over 42 per cent of Canadians aged 20 to 29 still live in their parental home (up from 32 per cent in 1991 and nearly 27 per cent in 1981), and the unemployment rate of Ontarians between 15 and 24 is only 17 per cent, it’s not hard to see why this is imperative. While the couple acknowledges the range of programs that are available, they also point out that they have been designed and scheduled for Crown wards exclusively. Ignite the Spark ensures the activities these children get into are the same as every other child. It may be a small thing, but it makes a huge difference: for a few hours, these children can “have a break from the struggles, a break from the pain and grief,” says Weissman-Daniels.

“What’s extraordinary about Mark and Andrea is how they could not simply retreat into their own happiness. Instead, they actively went out to fundamentally give every child in foster care a chance to find their own special ‘spark,’” says television reporter Anne Mroczkowski, who co-hosted the inaugural Spark Gala in 2011 and its followup in 2012.

Linton Carter, chief development officer of the Children’s Aid Foundation, agrees. “Their greatest qualities are their compassion and dedication to the causes they care about and their belief in the ability of the philanthropy community to bring about real change for kids in need,” she says.

A few days after the interview, Weissman-Daniels found herself by her daughter’s bedside. The next morning she would be taking her to the hospital for an emergency ultrasound to investigate an ongoing medical issue. The two shared a moment that put Weissman-Daniels and her husband’s motivation into perspective: their daughter lowered her defences and placed her trust in her adopted mother. Weissman-Daniels reached out via email to share this story and to put into context the emotions of adopting a child and why community support is needed.

She writes: “I started the Ignite the Spark Fund and continue to campaign for it not because I enjoy asking for money from people, not because I want attention and certainly not because I want to throw parties. I do it because it simply has to be done … My dream is to have someone step up with a tremendous financial gift that will ensure our fund will run until such a time as all Canadian children have found loving homes. On that day, I will rejoice and never need to put on another gown again.”

No Comment