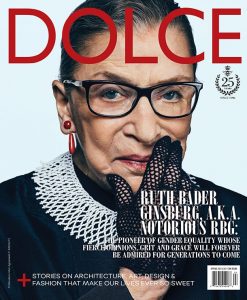

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: The Pursuit Of Social Justice

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s intent, her raison d’être, was clear: all men and all women, regardless of gender, race or creed, must be treated equally without fail.

Of the many things Ruth Bader Ginsburg, famously known as “Notorious RBG” (a nod to the famed American Rapper The Notorious B.I.G., also known as “Biggie Smalls”) was celebrated for, and, in fact, was emulated for, were her many and varied statement necklaces. RBG, only the second woman to be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States, was an associate justice of that court from 1993 until her passing in 2020. (The first woman, Sandra Day O’Connor, was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1981 by then-president, Ronald Reagan.)

But make no mistake: while these necklaces, also known as collars, might originally have been seen as fashion statements, a way to dress up her judicial black robes, anyone in the know, anyone in RBG’s circle, knew that these were no ordinary pieces of jewelry that she wore to court on important days. Known as jabots, RBG’s necklaces glinted in the courtroom lights, metaphoric and steely declarations of her unflinching opinions on decisions handed down by the Supreme Court.

Arguably RBG’s most renowned jabot was her dissent collar, a heavily jewel-studded necklace which she wore when she was proclaiming her condemnation and disapproval — her dissent — to a decision handed down by the Supreme Court. The fact that RBG would speak her dissent is unusual in itself; announcing a majority opinion in the court chamber is custom, but reading aloud in dissent is rare.1 And so, the dissent collar, that RBG wore on the day after Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential win speaks volumes without uttering a word. Just as intriguingly, it was the yellow jabot, with its thin bejewelled strips extending symmetrically from the collar, that RBG chose to wear to Barack Obama’s first address to a joint session of the U.S. Congress, on December 31, 2005.

“In every good marriage it helps sometimes to be a little deaf” – Evelyn Ginsburg

So, who is Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and how did this diminutive woman who fought and won myriad impactful battles on the stage of equality, especially as it relates to women, get tagged to the phenomena that is The Notorious B.I.G.?

Shana Knizhnik, co-author with Irin Carmon of Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (2015), is a public defender working in the criminal defence practice of the Legal Aid Society of New York City. It is she who was the original master-maker behind the idea of linking the rapper’s B.I.G. acronym to that of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“I started the Notorious RBG movement on Tumblr back in 2013. I wanted it to have a sense of irreverence and fun,” Knizhnik says. “It was a spur-of-the-moment response to recognize a moment in time in 2013, in large part stemming from the Shelby County vs. Holder voting rights case. The majority opinion in that case rolled back the 1965 Voting Rights Act’s protections, which would inherently impact the ability of certain communities to vote. RBG made it clear that this action would erode the rights of people of colour, poor people and other marginalized populations. And while B.I.G. and RBG are two people who could not be any more different on so many fronts, their words, in different ways, both spoke truth to power.”

Famously, near the end of her dissent in the Shelby County case, RBG explained why the regional protections of the Voting Rights Act were still necessary. “Throwing out pre-clearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”2

It is important to understand RBG’s background and what the defining experiences were that drove her to be a tireless advocate for women’s rights and equality well into her eighties, an age when most people put down their gauntlets in favour of a more sedate lifestyle.

Born to Jewish parents on March 15, 1933, Ruth, nicknamed “Kiki” by her older sister, was a cellist and a high-school cheerleader whose young life was steeped in sorrow. She lost her two-year-old sister to meningitis when she was 13, and tragically the day before she was to graduate from high school, RBG’s beloved mother, Celia, succumbed to cancer.

But Celia’s counsel to her daughter stuck: “Hold fast to your convictions and your self-respect, be a good teacher, but don’t snap back in anger,”1 advice that RBG followed her entire life by advocating for what she believed in and creating powerful environments in which the people she was championing thrived.

In fall 1950, RBG attended first-year classes at Cornell University in New York. While there, a professor at the university was targeted by Senator McCarthy’s Subcommittee and indicted or refusing to name fellow Marxist members of a study group. When it was pointed out to RBG that a lawyer had come to the professor’s rescue, she decided that the championing of people’s rights would be an ideal fit for her.

In her senior year, RBG met her soul mate and future husband, Marty Ginsburg, who ultimately was the one instrumental in getting RBG appointed to the Supreme Court.

Societal values at the time that RBG and Marty got married were pinned to what we now consider archaic tenets. Once married, a woman, if she was working, was forced to quit her job, stay home and become a housewife, her sole purpose being a wife and prolific mother. (Enterprising women were known to keep their marriage a secret from their employer, so they could continue working.) But neither RBG nor Marty were interested in the notion of a woman being subservient to a man; they were equal partners in life, and that was the way it was going to be. After ruling out both medical school and Harvard Business School — namely because women were not allowed — the couple applied and were accepted into Harvard Law School.

The couple now had their first child, Jane, and RBG wasn’t sure that she could handle both the demands of law school and the raising of a toddler. But the counsel she received from Morris, Marty’s father, helped set RBG’s course.

“If you don’t want to go to law school, you have the best reason in the world, and no one would think less of you. But, if you really want to go to law school, you will stop feeling sorry for yourself. You will find a way,” Marty told her.1

And indeed, that is what RBG did, albeit with a lot of challenges along the way.

Harvard Law School, long a bastion for men, was comprised of 500 men and nine women when RBG attended. Shamefully, women, a whispered presence in the school’s hallowed halls, did not have access to any bathrooms, nor were they allowed to use some of the school’s reading rooms, facts that today’s women cannot even begin to imagine.

Between studying the law and raising a toddler, life was busy but good. And along the way, RBG became one of the first women members of the Harvard Law Review.

Tragedy struck, however, when Marty was diagnosed with testicular cancer. He was extremely ill and extremely weak. Resolute and undeterred, RBG went to her own classes while recruiting note-takers in Marty’s, notes that she would type up for her husband to study while he dealt with his illness. Against unmitigated odds, Marty graduated with his law degree that year. RBG transferred her studies to Columbia Law School, where she graduated in a tie for first place.

“RBG’s work ethic was incomparable,” says Knizhnik. “When my colleague and I were writing the RBG book, I was a law student, and Irin was working full time. I saw the work and intensity it takes to write a book on top of studying, so just imagine what RBG endured. She was and is an inspiration to me. RBG could get by with just a few hours’ sleep, and, in fact, was known on the Supreme Court for being a night owl, sending messages very early in the morning to staff.”

RBG’s fights for equality on a grand scale, her mission to educate and her determination to be a change-maker are legendary. She was a co-founder of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and championed women’s rights cases (and some men’s, as well) right up to the Supreme Court, forever changing the face of the constitution as it relates to gender equality.

Some of the many cases that RBG defended in court, ones that made the most impact, include the 1996 Virginia Military Institute court case, which challenged the all-male admissions policy at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). The court, led by Justice Ginsburg, required the state-funded school accept women for admission. In the opinion, United States vs. Virginia, Ginsburg wrote that “generalizations about ‘the way women are,’ estimates of what is appropriate for most women, no longer justify denying opportunity to women whose talent and capacity place them outside the average description.”

“The majority opinion in the VMI case is perhaps the best-known and most important majority opinion Justice Ginsburg has penned in her 24 years [as at 2017, in total RBG served on the Supreme Court for 27 years] on the Supreme Court,” says Steve Vladeck, CNN Supreme Court analyst and professor of law at the University of Texas School of Law. “That case, more than any other, epitomized the justice’s effort to establish true sex equality as a fundamental constitutional norm, and its effects are continuing to reverberate today.”3

In a more recent case in 2020, one whose oral arguments Ginsburg participated in from a hospital bed, dealt with the Trump administration’s expanding exemptions for employers who had religious or moral objections to complying with the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate.

In her dissent, Ginsburg lambasted the court for “[leaving] women workers to fend for themselves,” in a case where the justices struck down the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate.

“Today, for the first time, the Court casts totally aside countervailing rights and interests in its zeal to secure religious rights to the nth degree,” Ginsburg wrote in dissent. She also noted that the government had acknowledged that the rules around the reduction of contraceptive coverage would cause thousands of women — “between 70,500 and 126,400 women of childbearing age,” — to lose coverage.3

Legalese and causes aside, who was Ruth Bader Ginsburg, what was she like beneath her collection of gleaming multicoloured collars, iconographic eyewear and the hair that was famously tucked into a severe bun at the nape of her neck, held there by a scrunchie? Who was the courageous woman behind the metaphoric coats of armour that deflected all attempts to silence her unflinching criticisms in the pursuit of the greater good?

Knizhnik shares a charming story of what it was like for her to sit beside RBG at Irin Carmon and Ari Richter’s wedding in 2017.

“I sat beside Justice Ginsburg at Irin’s wedding reception; it was the most stressful meal I have ever had,” Knizhnik, who is an accomplished lawyer herself, says laughingly. “I made, prior to the wedding, a list of conversation points to refer to, as RBG was not the most talkative person. She was soft spoken and was very deliberate with her words. Her clerks used to say that they had a five-second rule, that if Ruth stopped talking, you had to wait five seconds to make sure she was finished speaking — she was that deliberate with her words.” (RBG also officiated at Knizhnik’s New York legal wedding ceremony in September 2019.)

At first glance, R.B.G.’s persona might be interpreted as severe, possibly unapproachable, but she was known for her compassion and open-mindedness, and so she gamely embraced the “Notorious RBG” moniker.

“I met RBG in her chambers in the fall of 2014 and gave her a framed ‘Notorious RBG’ poster,” Knizhnik says.

The fact that the rapper and the Supreme Court justice were both Brooklynites probably didn’t hurt, either. In fact, in a 2015 interview with NPR, “Ginsburg admitted to being quite a fan of her new nickname, handing out T-shirts with the title to friends and fans alike.”4

RBG’s popularity grew exponentially, and over the years she became a cultural phenomenon, with Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” featuring an RBG character in a recurring role. Too, there was a 2018 movie made of RBG’s life called On the Basis of Sex.

An avid fan of the opera, RBG famously said, “If I had any talent in the world, any talent that God could give me, I would be a great diva.” (As it relates to the opera.)

While she didn’t get a chance to sing opera, RBG did appear on-stage as an extra on three different occasions, including Ariadne auf Naxos, where RBG batted a fan and wore a white wig.1 On another occasion, in 2013, she, along with three judicial colleagues, appeared in a production of Die Fledermaus, where they were introduced as “three guests supreme from the Court Supreme.” In fact, RBG went on to oversee twice-annual opera and instrumental recitals at the Court, because, she said, they “provide a most pleasant pause from the court’s heavy occupations.”1

As her popularity grew, RBG memes and her gift for phrases that resonated exploded.

There were quotes where RBG talked directly to women and their need to be independent, their need to claim their gender equality rights: “Women belong in all places where decisions are being made. It shouldn’t be that women are the exception.”

There are also RBG’s forceful appeals that encouraged everyone to work together in partnership and harmony, rather than divisiveness: “Fight for the things that you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.”

And, of course, the oft-quoted advice from RBG’s mother-in-law, Evelyn, on how to sustain a successful marriage: “In every good marriage, it helps sometimes to be a little deaf.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died of metastatic pancreatic cancer on September 18, 2020. She was 87 years old. Even in death, she made history, becoming both the first woman and the first Jewish person to lie in state at the United States Capitol Building. Her legacy of impactful rulings, ones that she made over her 27 years as a Supreme Court judge, will continue to be felt throughout many generations to come. The effects of RBG’s unrelenting advocacy for women and equality for people of all races were a clarion call of hopeful and positive activism, the likes of which the male bastions of politics have never before seen.

“It is impossible to give Ruth enough credit for opening up the doors that she did for all women. As a millennial, it is difficult for me to imagine being one of only nine women in a class of 500 at Harvard Law School. Justice Ginsburg inspired leagues of women and men to fight for equality based on gender, race and basic civil rights,” Knizhnik says. “As Frank Chi and Aminatou Sow said in the stickers they created at the same time Notorious RBG started, “‘Can’t Spell Truth Without Ruth.’”

1. Carmon, Irin and Shana Knizhnik. Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. New York: Dey Street Books, 2015, p. 6.

2. Michigan Law, University of Michigan, Ellen D. Katz. Justice Ginsburg’s Umbrella. Accessed via https://repository.law.umich.edu/book_chapters/81/.

3. CNN Politics. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s most notable Supreme Court decisions and dissents.” September 18, 2020. Accessed

via www.cnn.com/2020/09/18/politics/rbg-supreme-courtdecisions-dissents/index.html.

4. Okayplayer. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg was Proud to Share a Nickname with The Notorious B.I.G.” Accessed via www.okayplayer.com/culture/ruth-bader-ginsburg-nicknames-notorious-rbgnotorious-b-i-g.html.

From NOTORIOUS RBG by Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik, published by Dey Street Books. Copyright© 2015 by Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollinsPublishers

Page 3

It was Chief Justice John Roberts’s turn to announce an opinion he had assigned himself. The case was Shelby County v. Holder, a challenge to the constitutionality of a major portion of the Voting Rights Act.

Roberts has an amiable Midwestern affect and a knack for simple but elegant phrases that had served him well when he was a lawyer arguing before the justices. “Any racial discrimination in voting is too much,” Roberts declared that morning. “But our country has changed in the last fifty years.”

One of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation of the twentieth century had been born of violent images: the faces of murdered civil rights activists in Philadelphia, Mississippi; Alabama state troopers shattering the skull of young John Lewis on a bridge in Selma. But for this new challenge to voting rights that came from sixty miles from Selma, Roberts had a more comforting picture to offer the country. High black voter turnout had elected Barack Obama. There were black mayors in Alabama and Mississippi. The protections Congress had reauthorized only a few years earlier were no longer justifiable. Racism was pretty much over now, and everyone could just move on.

RBG waited quietly for her turn. Announcing a majority opinion in the court chamber is custom, but reading aloud in dissent is rare. It’s like pulling the fire alarm, a public shaming of the majority that you want the world to hear. Only twenty-four hours earlier, RBG had sounded the alarm by reading two dissents from the bench, one in an affirmative action case and another for two workplace discrimination cases. As she had condemned “the court’s disregard for the realities of the workplace,” Alito, who had written the majority opinion, had rolled his eyes and shook his head. His behavior was unheard of disrespect at the court.

Page 31, 32

Where Kiki was shy and contained, Marty was the life of the party.

His father, Morris, had risen through the garment industry to become vice president of Federated Department Stores; his mother, Evelyn, was an operagoer who quickly took her son’s motherless girlfriend under her wing. Kiki became a regular at the Ginsburg home on Long Island. She worked one summer at A&S, one of Federated’s stores, and on those suburban streets, she failed her driving test five times before passing the sixth.

Just because Evelyn didn’t work outside the home didn’t mean Marty expected the same from his future wife. He wanted them to marry and keep on working together, at Harvard. His idea was, Marty later recalled, “to be in the same discipline so there would be something you could talk about, bounce ideas off of, know what each other was doing, and we actually sat down and by process of elimination came up with the law.” Marty had dropped his chemistry major because it interfered with golf practice, so medical school was out. Harvard Business School didn’t accept women. So they settled on law. “I have thought deep in my heart,” Marty would confess forty years later, “that Ruth always intended that to be the case.”

They both made it into Harvard Law School. Marty, a year older, enrolled immediately while Kiki stayed in Ithaca to finish at Cornell. In June 1954, they married in the Ginsburgs’ living room, just days after Kiki’s graduation from Cornell. There were eighteen people present, because in Judaism that number symbolizes life. Moments before the ceremony, as Kiki made last minute arrangements, Evelyn asked her to come with her to the bedroom. “Dear,” said Evelyn, whom Kiki would soon call Mother, “I’m going to tell you the secret of a happy marriage. It helps sometimes to be a little deaf.” In her outstretched hand were a pair of earplugs.

It took some time for RBG to understand what Evelyn was trying to tell her. During the honeymoon in Europe, her first time outside of the country, it became clear.

“My mother in-law meant simply this,” RBG said. “Sometimes people say unkind or thoughtless things, and when they do, it is best to be a little hard of hearing—to tune out and not snap back in anger or impatience.”

Page 167

Being an opera fan on the highest court has its perks, including at least three onstage turns as an extra. One of these was with Scalia, in Ariadne auf Naxos, where RBG batted a fan and wore a white wig. One singer hopped on Scalia’s lap. In a 2003 production of Die Fledermaus, she, Kennedy, and Breyer surprised everyone onstage when they were introduced as “three guests supreme from the Court Supreme.” The best part? “Domingo was about two feet from me—it was like an electrical shock ran through me,” RBG said. RBG now oversees twice-annual opera and instrumental recitals at the court. As she put it in a speech, they “provide a most pleasant pause from the court’s heavy occupations.”

Page 178 through and including 181

HOW TO BE LIKE RBG

WORK FOR WHAT YOU BELIEVE IN

RBG saw injustice in the world and she used her abilities to help change it. Although the forces of “apathy, selfishness, or anxiety that one is already overextended” are “not easy to surmount,” as she puts it, RBG urges us “to repair tears in [our] communities, nation, and world, and in the lives of the poor, the forgotten, the people held back because they are members of disadvantaged or distrusted minorities.”

BUT PICK YOUR BATTLES

RBG survived the indignities of pre-feminist life mostly by deciding that anger was counterproductive. “This wonderful woman whose statue I have in my chambers, Eleanor Roosevelt, said, ‘Anger, resentment, envy. These are emotions that just sap your energy,” RBG says. “They’re not productive and don’t get you anyplace, so get over it.’” To be like RBG in dissent, save your public anger for when there’s lots at stake and when you’ve tried everything else.

AND DON’T BURN YOUR BRIDGES

“Fight for the things that you care about,” RBG advised young women, “but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.” RBG always tells her clerks to paint the other side’s arguments in the best light, avoiding personal insults. She is painstaking in presenting facts, on the theory that the truth is weapon enough.

DON’T BE AFRAID TO TAKE CHARGE

RBG believes that “women belong in all places where decisions are being made.” Back when many feminists were arguing that women spoke in a different voice, RBG observed the flaw in describing women as inherently different or even purer than men: “To stay uncorrupted, the argument goes, women must avoid internalizing ‘establishment’ values; they must not capitalize on opportunity presented by an illegitimate opportunity structure.” RBG has used her establishment positions to fight for structural change and on behalf of the oppressed. More recently, she has also united the court’s liberals under her leadership.

THINK ABOUT WHAT YOU WANT, THEN DO THE WORK

When a young RBG suddenly was faced with the prospect of starting law school with a toddler, her father-in-law told her, “If you really want to study the law, you will find a way. You will do it.” RBG says, “I’ve approached everything since then that way. Do I want this or not? And if I do, I’ll do it.”

BUT THEN ENJOY WHAT MAKES YOU HAPPY

RBG gets out—a lot.

BRING ALONG YOUR CREW

“RBG was never in it to be the only one, to be the superstar that nobody could match,” says fellow feminist attorney Marcia Greenberger. RBG mentored legions of feminist lawyers and happily welcomed Sotomayor and Kagan to the Supreme Court.

HAVE A SENSE OF HUMOR

A little goes a long way.

“It Is Impossible To Give Ruth Enough Credit For Opening Up The Doors That She Did For All Women” — Shana Knizhnik