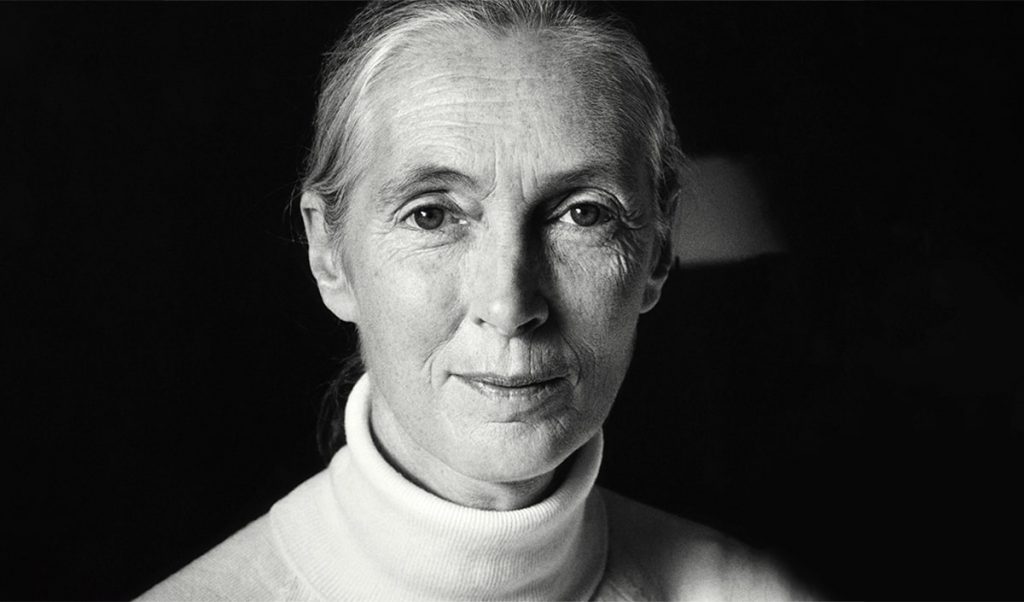

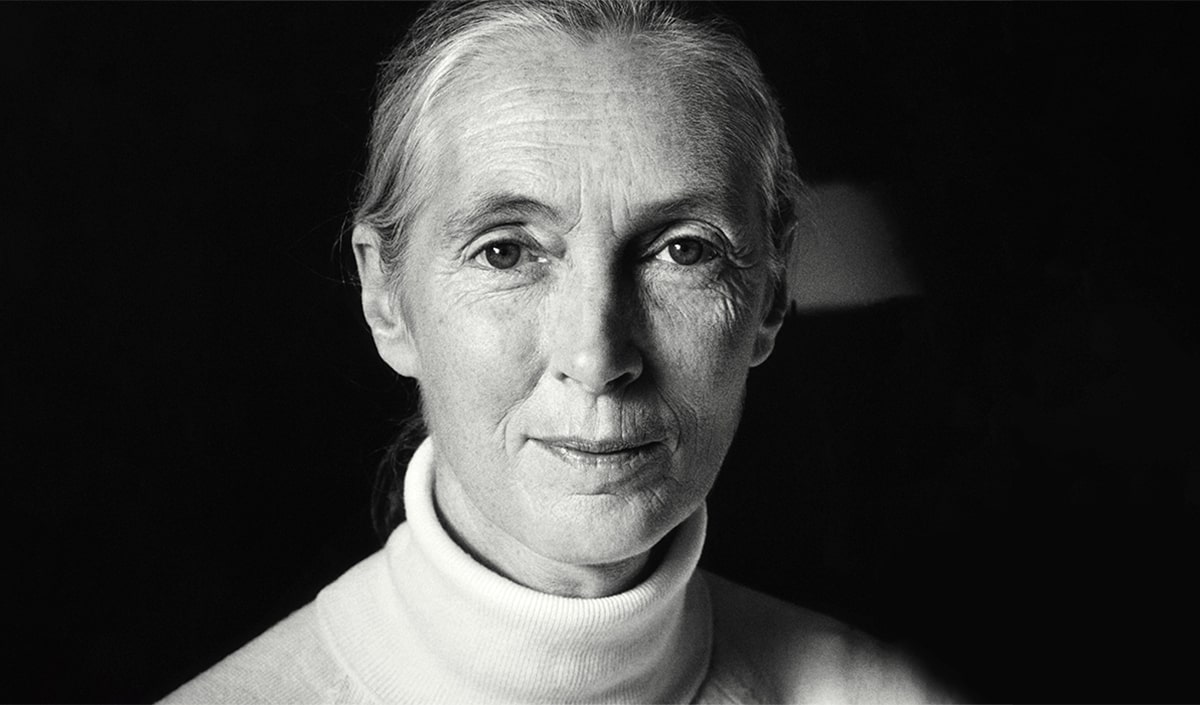

Thank you, Goodall

Jane Goodall has opened our minds, hearts, souls and senses to the fact that we share this planet with other living animals, for which we shall all be eternally grateful.

In retrospect and to our collective embarrassment, it’s almost impossible to believe we’ve all been so blatantly ignorant. As one species occupying this singular planet, we humans were almost completely oblivious to the other species occupying our rock — those animals. The human species claims to have the intellect of reason, curiosity, logic, invention and self-preservation, but seemingly lacks that one important component: awareness. Awareness that there was something else in the room.

Until Jane Goodall.

The list of people who have influenced the modern world is very short, but Goodall is on that list. And we all owe her a debt of deepest gratitude for opening our eyes to the fact that animals have an equal place on this planet and should be treated with kindness, dignity, compassion and respect.

Before Goodall entered our collective consciousness, wild animals were to be avoided unless we had captured them and put them in cages or in a circus. Chimps were sort of cute and even funnier little guys if they rode a little tricycle and smoked a cigar. Elephants looked menacing, but when they walked around a circus ring with trunks wrapped around tails, they were rather docile beasts.

We even put wild animals in our cartoons and festooned them with funny voices. Nothing wrong with laughing along with mischievous hippos, crocodiles or a Curious George on a Saturday morning. We made animals into characters.

In actuality during those years, we really knew nothing about the “other” species with which we share Earth, and we didn’t have to. We were in charge here, thank you very much.

How blind we were. “Ecosystem” and “endangered” were only good scores in Scrabble. The balance of nature was never a consideration.

Until Jane Goodall.

When she burst upon the collective reality in the 1960s, she showed us how animals not only live, but also feel, fear and protect their families. Just like us. And by doing that, she showed us, to our amazement, the many similarities we have with the other animals occupying our planet. They protect their homes and their families, they search for food, can play with one another and feel pain. Turns out, they’re just like us. And she taught us how to communicate with them.

And the world’s nations were humbled and gave thanks to her for exposing this reality — buried in all these generations until she came along. The latest was Canada, which, in November 2020, introduced the Jane Goodall Act, which, if passed, will protect great apes, elephants and other wild animals in captivity and will ban the import of elephant ivory and hunting trophies into Canada, continuing the influence and impact Goodall has had in the world.

“Jane Goodall is a hero who inspires us to do better by all creatures of Creation with whom we share this earth,” says Senator Murray Sinclair, who introduced this notable bill. “Named in Goodall’s honour, this bill will create laws to better protect many animals, reflecting Indigenous values of respect and stewardship.”

“We live in a time, and a world, where respecting and caring for one another and our shared planet is the only way forward,” says Goodall. “As humans around the world accept that animals are sentient beings, there is a growing call for improved living conditions and treatment of captive animals. This bill being tabled by Senator Sinclair has the best interests of captive animals in mind. And the proposed ban on elephant ivory products and hunting trophies in Canada will decrease the worldwide market which fuels the senseless slaughter of endangered species. I commend Senator Sinclair for tabling this bill and I am honoured that it bears my name.”

When you get a bill of law named after you, you’ve had an impact. It is testament to Goodall’s almost mystical influence on all of us in making us think of the animal world. She was successful in this by her endearing and natural way of communications.

Albert Einstein knew, well, pretty much everything, but he was challenged in explaining it to the masses, because his subject matter was so dense that the rest of us mere mortals often wondered what the heck this guy was talking about. No so with Goodall.

Her real words, understandable explanations and authentic empathy for the animals she was studying broke through. Whether she was that “crazy lady who rolled around with gorillas in the jungles of Africa” or that lady who bantered late at night with Johnny Carson, she brought the reality and plight of the animal kingdom into our living rooms and onto our bookshelves, having authored more than two dozen books.

She understood optics and the power of visual mass communications and television in the 1960s, and through National Geographic TV specials or feature articles, she made sure we got it. She recognized the power of the camera and would have no problem snuggling up in the arms of her adopted gorilla deep in the rainforest if she thought it could communicate her message that we had to pay attention to these vital members of our natural ecosystem. That these were natural feeling species — just like us. Goodall brought the raw reality of the jungle and humankind’s threats to the animal kingdom to our safe, neat and tidy suburban doorstep.

Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall was born in 1934 in Hampstead, London. As a child, as an alternative to a teddy bear, Goodall’s father gave her a stuffed chimpanzee named Jubilee, and she carried it with her everywhere. Goodall has said her fondness for this figure started her early love of animals. “My mother’s friends were horrified by this toy, thinking it would frighten me and give me nightmares,” she recalls. Today, Jubilee still sits on Goodall’s dresser in London.

“It Isn’t Only Human Beings Who Have Personality, Who Are Capable Of Rational Thought And Emotions Like Joy And Sorrow” — Jane Goodall

Her love of animals led her to a friend’s farm in the Kenya highlands in 1957, where she obtained work as a secretary. There, she had the audacity to telephone noted Kenyan archeologist Louis Leakey, with no other thought than to have a discussion about animals. Unknown to her, Leakey was looking for a chimpanzee researcher and proposed Goodall work for him as a secretary, where he grew increasingly impressed by Goodall’s work and natural curiosity.

On July 14, 1960, Goodall first set foot in what is now known as Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania to launch her pioneering research with wild chimpanzees. She was just 26 years old. With his encouragement, Leakey, who arranged her funding, sent Goodall (who had no university degree) to the University of Cambridge, where she obtained a PhD. She became only the eighth person to be allowed to study for a PhD there without first having obtained a BA or B.Sc. Her groundbreaking doctoral thesis, “Behaviour of free-living chimpanzees,” was completed in 1965, detailing her first five years of study at the Gombe Reserve.

In 1977, she founded the Jane Goodall Institute, which continues to support the research at Gombe. Now with 31 offices around the world, Goodall and the institute continue to be widely recognized for effective community-centred conservation.

Goodall is a leader who continually looks for ways to make a difference. In 1991, after meeting a group of Tanzanian teenagers to discuss community problems, she created Roots & Shoots, a program dedicated to inspire young people to take action in their communities. It has since grown to include approximately 150,000 individuals in more than 50 countries.

Before the pandemic, Goodall travelled an average of 300 days per year speaking to youth and world leaders about the threats facing chimpanzees, other environmental issues and her reasons for hope that we will eventually solve the problems that humans have imposed upon Earth. Wherever she goes, she urges audiences to recognize their personal power and responsibility to effect positive change through lifestyle change, consumer action and activism.

“You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make,” Goodall has famously said.

She has done just that in this country through the Jane Goodall Institute of Canada, and the Jane Goodall Act elevates her influence even further and in a lawful and meaningful way. The act would:

– Ban new captivity of great apes and elephants unless licensed for their best interests, including individual welfare and conservation, or non-harmful scientific research.

– Ban the use of great apes and elephants in performance, including elephant rides.

– Establish legal standing for great apes, elephants, whales and dolphins in sentencing for captivity offences, allowing court orders for relocation or improved conditions.

– Ban the import of elephant ivory and hunting trophies.

– Empower government to extend all the protections to other species of captive, non-domesticated animals — such as big cats — by regulation with the “Noah Clause.”

With the Noah Clause in Canada, the bill authorizes the federal cabinet to extend the legal protections to additional captive, non-domesticated species through regulation. The government could protect “designated animals” after consulting with experts on the species’ ability to live a good life in captivity.

We may not think of Canada as a haven for exotic animals, but it is estimated there are approximately 1.5 million privately owned exotic animals in the country, including nearly 4,000 big cats. Senator Sinclair, in introducing the Jane Goodall Act, pointed to the topic of big cats and the documentary Tiger King. “I am excited this bill can protect many animals, based on science,” says Senator Sinclair. “If the Jane Goodall Act becomes law, I hope the government protects big cats to prevent the kind of shameful exploitation seen in Tiger King.”

In Canada, there are 33 great apes in captivity made up of nine chimpanzees, 18 gorillas and six orangutans. There are also 20 elephants living in captivity in Canada, with some wildlife parks using elephants for performances and rides.

“This legislation is not necessarily at odds with all zoos — it is for animals,” says Senator Sinclair. “I look to credible zoos as potential partners and hope the bill generates dialogue and innovation, with consensus on putting animals first.”

That is what Goodall has done all her life since those early days in Tanzania, observing the lives of wild chimpanzees. Instead of numbering the chimpanzees she observed, she gave them names, such as Fifi and David Greybeard, and found them to have individual personalities — an unconventional thought at the time. “It isn’t only human beings who have personality, who are capable of rational thought and emotions like joy and sorrow,” she has observed.

Goodall’s extensive time in the bush allowed her to witness such behaviours as hugs, kisses, pats on the back and even tickling — what we would consider “human” actions. Goodall insists that these gestures are evidence of “the close, supportive, affectionate bonds that develop between family members and other individuals within a community, which can persist throughout a lifespan of more than 50 years,” which she has written in her studies.

“In what terms should we think of these beings, non-human yet possessing so very many humanlike characteristics?” she once asked. “How should we treat them? Surely, we should treat them with the same consideration and kindness as we show to other humans; and as we recognize human rights, so too should we recognize the rights of the great apes? Yes. The least I can do is speak out for those who cannot speak for themselves.”

The chimps would also take twigs from trees and strip off the leaves to make the twig more effective, a modification that is the rudimentary beginnings of toolmaking. In response to Goodall’s findings, her mentor, Louis Leakey, wrote: “We must now redefine man, redefine tool, or accept chimpanzees as human!”

It was revolutionary thinking, and by pulling back the dense foliage and showing it to us on television, Goodall changed our reality in how we think about the animal kingdom. Much like Jacques Cousteau revealed the wonders of the world below the waves, Goodall’s pioneering work and everyday observations and commentaries made human beings reconsider our place in the pecking order of the planet.

Her work also first revealed to us humankind’s impact on the natural habitats of animals in countries we would only casually read about in a back-dated magazine in a doctor’s waiting room. The dangers of deforestation, logging roads, poaching and mining for minerals in remote regions of the world are all having a severely negative effect on the balance of nature. “How could a species just disappear from the world?” we wondered. Goodall showed us how.

“We have the choice to use the gift of our life to make the world a better place,” says Goodall. “The greatest danger to our future is apathy.”

Her work continues today through the Jane Goodall Institute, where she remains an outspoken environmental advocate, speaking on the effects of climate change on endangered species, such as chimpanzees. Goodall, alongside her foundation, collaborated with NASA to use satellite imagery from the Landsat series to remedy the effects of deforestation on chimpanzees and local communities in Western Africa by offering the villagers information on how to reduce activity and preserve their environment.

Despite the environmental challenges and animal threats she has seen, Goodall remains an optimist and has stated “Four Reasons for Hope,” based upon four things she has observed: the power of the human brain; the strength of our spirit; the resilience of nature; and the determination of young people.

“Surely, we can use our problem-solving abilities, our brains, to find ways to live in harmony with nature,” she says about the human brain. “Millions of people worldwide are beginning to realize each of us has a responsibility to the environment and our descendants.”

“My second reason is that there are so many people who have dreamed seemingly unattainable dreams, and because they never gave up, achieve their goals against all odds,” says Goodall, when championing the human spirit. “I meet so many incredible and amazing human beings. They inspire me. They inspire those around them.”

“What You Do Makes A Difference, And You Have To Decide What Kind Of Difference You Want To Make” — Jane Goodall

Speaking about the resilience of nature she observes, says Goodall: “I have visited Nagasaki, site of the second atomic bomb. Scientists predicted that nothing would grow there for at least 30 years. But I carry a leaf from a large tree that survived the bombing. I have seen such renewals time and again, including animal species brought back from the brink of extinction.”

“My final reason for hope lies in the tremendous energy, enthusiasm and commitment of young people around the world,” says Goodall. “Young people, when informed and empowered, when they realize that what they do truly makes a difference, can indeed change the world.”

In August 2019, Goodall was honoured for her contributions to science with a bronze sculpture in midtown Manhattan, N.Y., alongside nine other women, part of the Statues for Equality project. Even in 2020, continuing her organization’s work on the environment, Goodall has vowed to plant five million trees, part of the One Trillion Tree initiative founded by the World Economic Forum.

Goodall also sees the current global pandemic as another sign to protect the natural balance of life on this one good Earth. She has been sharing her hope for the future, where interconnection between human health, animal health and environmental health is understood and respected. “To avoid another pandemic, we must have more respect for the natural world,” she has written.

Today, Jane Goodall is 86 years old and can reflect upon her life, as a human, helping animals, from her beloved first stuffed chimpanzee Jubilee to moving world governments to enact long-overdue laws and regulations to protect the animal kingdom and the environment.

In a video produced by National Geographic Television to celebrate her 80th birthday, Goodall cautioned that we not get too overwhelmed by the tasks at hand and to keep them small and manageable.

“If you think globally, you become filled with gloom,” she says. “But if you take a little piece of the whole picture, my piece, our piece, [you think,] ‘This is what I can do here, I’m making a difference, and hey, wow, they’re making a difference over there, and so are they,’ and so gradually the pieces get filled in, and the world is a better place, because of you.”

The world is a better place because of Jane Goodall, by her bringing two species together on the only planet they know to co-exist, to understand each other, to appreciate each other, to respect each other.

Thank you, Goodall, for opening our eyes, our hearts and our souls to the animals.

Has there ever been a more influential life lived? Has there ever been a better mission served? Or a better message delivered?

Talk to the animals.

CHIMPANZEE CHAMPION AND INFLUENTIAL PRIMATOLOGIST JANE GOODALL, 86, ON …

… attending the University of Cambridge:

“I was nervous going to Cambridge in the U.K. and shocked when the professors told me that I shouldn’t have given the chimpanzees names; numbers were more scientific. I couldn’t talk about personality, mind or emotion, because those were unique to us.”

… climate change:

“One of the big problems, which is beginning to be understood, is that we really need to move toward a plant-based diet … an awful lot of water is used to get vegetable-to-animal protein. And then on top of all of that, all these billions of animals are producing methane gas, which is a very virulent greenhouse gas …

“The methane from all this animal agriculture is another really important aspect. So, something we can do is eat less meat or no meat or be a vegan even, as long as people do something — and think about it.”

… individual responsibility:

“The big message I take around is: every single person makes some impact on the planet every day. And you get to choose what you buy, where it comes from. But the thing you have to do first to make this work is to alleviate poverty. Because if you’re really poor, you’re going to cut down the last tree, because you’ve got to live. You’re going to take money to kill an elephant, because you have to survive.”

… what it means to be human:

“I suppose it’s because we’ve developed this language which has enabled us to talk about things that aren’t present. We are in a position to understand our relation to the rest of the planet. We can ask questions like, ‘Why am I here? And do I matter?’ And I think that’s what makes us different, that we can question the reason for existence. We can question why we’re on the planet, our role.”

… her first visit to Africa:

“I saved up money waitressing and then, when I was 23, I went to visit an old school friend living in Kenya … The idea was to stay for a year and see what happened. I got off the boat at Mombasa, and we drove up into the highlands. “The very first morning, there was a fresh leopard track on the farm, and I saw an aardvark on the road — I’ve never seen that since. And seeing a giraffe close up … however much you know giraffes, to see one in the wild for the first time feels prehistoric.”

… how her life’s work influenced her as a mother:

“A chimp mother … is patient, she is protective, but she is not overprotective — that is really important. She is tolerant, but she can impose discipline. She is affectionate. She plays. And the most important of all: she is supportive, so that if her kid gets into a fight, even if it is with a higher-ranking individual, she will not hesitate to go in and help.”

… fighting sexism in the scientific community:

“I had to work 10 times harder than the average man just to get the same level of recognition, but once I had made a name for myself, I let the data speak for me. I also realized early on, once I had started to gain some notoriety, that the future careers of many women rested on my shoulders … “If I could show them the way and open those doors for them, then it would be that much easier for the next generation of women scientists to break into their chosen fi eld in a substantial way.”